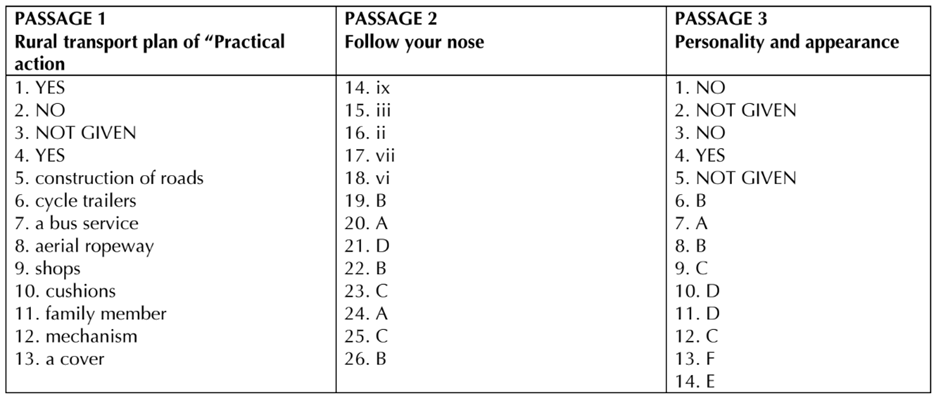

PASSAGE 1 Rural transport plan of “Practical action

For more than 40 years, Practical Action has worked with poor communities to identify the types of transport that work best, taking into consideration culture, needs and skills. With our technical and practical support, isolated rural communities can design, build and maintain their own solutions.

A

Whilst the focus of National Development Plans in the transport sector lies heavily in the areas of extending road networks and bridges, there are still major gaps identified in addressing the needs of poorer communities. There is a need to develop and promote the sustainable use of alternative transport systems and intermediate means of transportation (IMTs) that complement the linkages of poor people with road networks and other socio-economic infrastructures to improve their livelihoods.

B

On the other hand, the development of all weathered roads (only 30 percent of the rural population have access to this so far) and motorable bridges are very costly for a country with a small and stagnant economy. In addition, these interventions are not always favourable in all geographical contexts environmentally, socially and economically. More than 60 percent of the network is concentrated in the lowland areas of the country. Although there are a number of alternative ways by which transportation and mobility needs of rural communities in the hills can be addressed, a lack of clear government focus and policies, lack of fiscal and economic incentives, lack of adequate technical knowledge and manufacturing capacities have led to under- development of this alternative transport sub-sector including the provision of IMTs.

C

One of the major causes of poverty is isolation. Improving the access and mobility of the isolated poor paves the way for access to markets, services and opportunities. By improving transport poorer people are able to access markets where they can buy or sell goods for income, and make better use of essential services such as health and education. No proper roads or vehicles mean women and children are forced to spend many hours each day attending to their most basic needs, such as collecting water and firewood. This valuable time could be used to tend crops, care for the family, study or develop small business ideas to generate much-needed income. Road building

D

Without roads, rural communities are extremely restricted. Collecting water and firewood, and going to local markets is a huge task, therefore it is understandable that the construction of roads is a major priority for many rural communities. Practical Action is helping to improve rural access/transport infrastructures through the construction and rehabilitation of short rural roads, small bridges, culverts and other transport-related functions. The aim is to use methods that encourage community-driven development. This means villagers can improve their own lives through better access to markets, health care, education and other economic and social opportunities, as well as bringing improved services and supplies to the now-accessible villages. Driving forward new ideas

E

Practical Action and the communities we work with are constantly crafting and honing new ideas to help poor people. Cycle trailers have practical business use too, helping people carry their goods, such as vegetables and charcoal, to markets for sale. Not only that, but those on the poverty-line can earn a decent income by making, maintaining and operating bicycle taxis. With Practical Action’s know-how, Sri Lanka communities have been able to start a bus service and maintain the roads along which it travels. The impact has been remarkable. This service has put an end to rural people’s social isolation. Quick and affordable, it gives them a reliable way to travel to the nearest town; and now their children can get an education, making it far more likely they’ll find a path out of poverty. Practical Action is also an active member of many national and regional networks through which exchange of knowledge and advocating based on action research are carried out and one conspicuous example is the Lanka Organic Agriculture Movement. Sky-scraping transport system

F

For people who live in remote, mountainous areas, getting food to market in order to earn enough money to survive is a serious issue. The hills are so steep that travelling down them is dangerous. A porter can help but they are expensive, and it would still take hours or even a day. The journey can take so long that their goods start to perish and become worthless and less. Practical Action has developed an ingenious solution called an aerial ropeway. It can either operate by gravitation force or with the use of external power. The ropeway consists of two trolleys rolling over support tracks connected to a control cable in the middle which moves in a traditional flywheel system. The trolley at the top is loaded with goods and can take up to 120kg. This is pulled down to the station at the bottom, either by the force of gravity or by an external power. The other trolley at the bottom is, therefore, pulled upwards automatically. The external power can be produced by a micro-hydro system if access to an electricity grid is not an option. Bringing people on board

G

Practical Action developed a two-wheeled iron trailer that can be attached (via a hitch behind the seat) to a bicycle and be used to carry heavy loads (up to around 200 kgs) of food, water or even passengers. People can now carry three times as much as before and still pedal the bicycle. The cycle trailers are used for transporting goods by local producers, as ambulances, as mobile shops, and even as mobile libraries. They are made in small village workshops from iron tubing, which is cut, bent, welded and drilled to make the frame and wheels. Modifications are also carried out to the trailers in these workshops at the request of the buyers. The two- wheeled ‘ambulance’ is made from moulded metal, with standard rubber-tyred wheels. The “bed” section can be padded with cushions to make the patient comfortable, while the “seat” section allows a family member to attend to the patient during transit. A dedicated bicycle is needed to pull the ambulance trailer, so that other community members do not need to go without the bicycles they depend on in their daily lives. A joining mechanism allows for easy removal and attachment. In response to user comments, a cover has been designed that can be added to give protection to the patient and attendant in poor weather. Made of treated cotton, the cover is durable and waterproof.

Questions 1-4

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage ?

In boxes 1-4 on your answer sheet, write

YES if the statement is true

NO if the statement is false

NOT GIVEN if the information is not given in the passage

1/ A slow-developing economy often can not afford some road networks, especially for those used regardless of weather conditions.

2/ Rural communities’ officials know how to improve alternative transport technically.

3/ The primary aim for Practical Action to improve rural transport infrastructures is meant to increase the trade among villages.

4/ Lanka Organic Agriculture Movement provided service that Practical Action highly involved in.

Questions 5-8

Answer the questions below.

Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS AND/OR A NUMBER from the passage for each answer.

5/ What is the first duty for many rural communities to reach unrestricted development?

6/ What was one of the new ideas to help poor people carry their goods, such as vegetables and charcoal, to markets for sale?

7/ What service has put an end to rural people’s social isolation in Sri Lanka?

8/ What solution had been applied for people who live in remote mountainous areas getting food to market?

Questions 9-13

Complete the following summary of the paragraphs of Reading Passage.

Using NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the Reading Passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 9-13 on your answer sheet.

Besides normal transport task, changes are also implemented to the trailers in these workshops at the request of the buyers when it was used on a medical emergency or a moveable 9 ……………………..; ‘Ambulance’ is made from metal, with rubber wheels and drive-by another bicycle. When put with 10 ……………………..; in the two-wheeled ‘ambulance’, the patient can stay comfortable and which another 11 ……………………..;. can sit on caring for the patient in transport journey. In order to dismantle or attach other equipment, and assembling 12 ……………………..; is designed. Later, as users suggest, 13 ……………………..; has also been added to give protection to the patient.

PASSAGE 2 Follow your nose

A.

Aromatherapy is the most widely used complementary therapy in the National Health Service, and doctors use it most often for treating dementia. For elderly patients who have difficulty interacting verbally, and to whom conventional medicine has little to offer, aromatherapy can bring benefits in terms of better sleep, improved motivation, and less disturbed behaviour. So the thinking goes. But last year, a systematic review of health care databases found almost no evidence that aromatherapy is effective in the treatment of dementia. Other findings suggest that aromatherapy works only if you believe it will. In fact, the only research that has unequivocally shown it to have an effect has been carried out on animals.

B.

Behavioural studies have consistently shown that odours elicit emotional memories far more readily than other sensory cues. And earlier this year, Rachel Herz, of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, and colleagues peered into people’s heads using functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) to corroborate that. They scanned the brains of five women while they either looked at a photo of a bottle of perfume that evoked a pleasant memory for them, or smelled that perfume. One woman, for instance, remembered how as a child living in Paris—she would watch with excitement as her mother dressed to go out and sprayed herself with that perfume. The women themselves described the perfume as far more evocative than the photo, and Herz and co-workers found that the scent did indeed activate the amygdala and other brain regions associated with emotion processing far more strongly than the photograph. But the interesting thing was that the memory itself was no better recalled by the odour than by the picture. “People don’t remember any more detail or with any more clarity when the memory is recalled with an odour,” she says. “However, with the odour, you have this intense emotional feeling that’s really visceral.”

C.

That’s hardly surprising, Herz thinks, given how the brain has evolved. “The way I like to think about it is that emotion and olfaction are essentially the same thing,” she says. “The part of the brain that controls emotion literally grew out of the part of the brain that controls smell.” That, she says, probably explains why memories for odours that are associated with intense emotions are so strongly entrenched in us, because smell was initially a survival skill: a signal to approach or to avoid.

D.

Eric Vermetten, a psychiatrist at the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands, says that doctors have long known about the potential of smells to act as traumatic reminders, but the evidence has been largely anecdotal. Last year, he and others set out to document it by describing three cases of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in which patients reported either that a certain smell triggered their flashbacks, or that a smell was a feature of the flashback itself. The researchers concluded that odours could be made use of in exposure therapy, or for reconditioning patients’ fear responses.

E.

After Vermetten presented his findings at a conference, doctors in the audience told him how they had turned this association around and put it to good use. PTSD patients often undergo group therapy, but the therapy itself can expose them to traumatic reminders. “Some clinicians put a strip of vanilla or a strong, pleasant, everyday odorant such as coffee under their patients’ noses, so that they have this continuous olfactory stimulation.” says Vermetten. So armed, the patients seem to be better protected against flashbacks. It’s purely anecdotal, and nobody knows what’s happening in the brain, says Vermetten, but it’s possible that the neural pathways by which the odour elicits the pleasant, everyday memory override the fear-conditioned neural pathways that respond to verbal cues.

F.

According to Herz, the therapeutic potential of odours could lie in their very unreliability. She has shown with her perfume-bottle experiment that they don’t guarantee any better recall, even if the memories they elicit feel more real. And there’s plenty of research to show that our noses can be tricked, because being predominantly visual and verbal creatures, we put more faith in those other modalities. In 2001, for instance, Gil Morrot, of the National Institute for Agronomic Research in Montpellier, tricked 54 oenology students by secretly colouring a white wine with an odourless red dye just before they were asked to describe the odours of a range of red and white wines. The students described the coloured wine using terms typically reserved for red wines. What’s more, just like experts, they used terms alluding to the wine’s redness and darkness—visual rather than olfactory qualities. Smell, the researchers concluded, cannot be separated from the other senses.

G.

Last July, Jay Gottfried and Ray Dolan of the Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience in London took that research a step fur

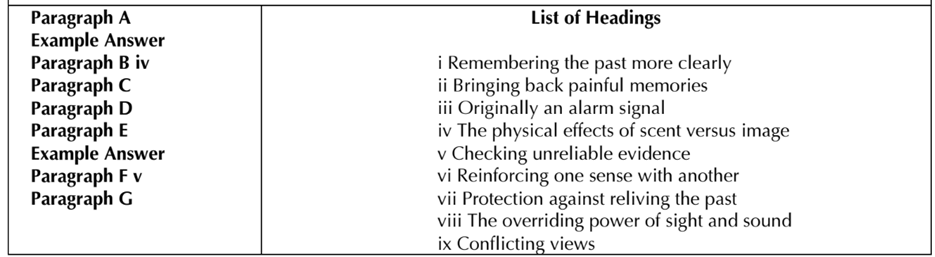

Questions 14-18

Reading Passage has seven paragraphs, A—G

Choose the correct heading for paragraph A, C, D, E and G from the list of headings below.

Write the correct number i—ix in boxes 14-18 on your answer sheet.

Questions 19 – 24

Look at the following findings (Questions 19-24) and the list of researchers

Match each finding with the correct researcher, A-D.

Write the correct letter, A-D, in boxes 19-24 on your answer sheet.

A. Rachel Hertz

B. Eric Vermetten

C. Gil Morrot

D. Jay Gottfried and Ray Dolan

NB You may use any letter more than once.

19/ Smell can trigger images of horrible events.

20/ Memory cannot get sharper by smell.

21/ When people are given an odour and a picture of something to learn, they will respond more quickly in naming the smell because the stimulus is stronger when two or more senses are involved.

22/ Pleasant smells counteract unpleasant recollections.

23/ It is impossible to isolate smell from visual cues.

24/ The part of brain that governs emotion is more stimulated by a smell than an image.

25/ In the article, what is the opinion about the conventional method of aromatherapy?

A. Aromatherapy is the use of essential oils extracted from plants.

B. Evidence has proved that aromatherapy is effective in treating dementia.

C. People who feel aromatherapy is effective believe it is useful.

D. Aromatherapy is especially helpful for elderly patients.

26/ What is Rachel Hertz’s conclusion?

A. The area of the brain which activates emotion has the same physiological structure as the part controlling olfaction.

B. We cannot depend on smell, and people have more confidence in sight and spoken or written words.

C. Odours can recall real memories even after the perfume-bottle experiment.

D. Smell has proved its therapeutic effect over a long time span.

PASSAGE 3 Personality and appearance

When Charles Darwin applied to be the “energetic young man” that Robert Fitzroy, the Beagle’s captain, sought as his gentleman companion, he was almost let down by a woeful shortcoming that was as plain as the nose on his face. Fitzroy believed in physiognomy—the idea that you can tell a person’s character from their appearance. As Darwin’s daughter Henrietta later recalled, Fitzroy had “made up his mind that no man with such a nose could have energy”. This was hardly the case. Fortunately, the rest of Darwin’s visage compensated for his sluggardly proboscis: “His brow saved him.”

The idea that a person’s character can be glimpsed in their face dates back to the ancient Greeks. It was most famously popularised in the late 18th century by the Swiss poet Johann Lavater, whose ideas became a talking point in intellectual circles. In Darwin’s day, they were more or less taken as given. It was only after the subject became associated with phrenology, which fell into disrepute in the late 19th century, that physiognomy was written off as pseudoscience.

First impressions are highly influential, despite the well-worn admonition not to judge a book by its cover. Within a tenth of a second of seeing an unfamiliar face we have already made a judgement about its owner’s character—caring, trustworthy, aggressive, extrovert, competent and so on. Once that snap judgement has formed, it is surprisingly hard to budge. People also act on these snap judgements. Politicians with competent- looking faces have a greater chance of being elected, and CEOs who look dominant are more likely to run a profitable company. There is also a well-established “attractiveness halo”. People seen as good-looking not only get the most valentines but are also judged to be more outgoing, socially competent, powerful, intelligent and healthy.

In 1966, psychologists at the University of Michigan asked 84 undergraduates who had never met before to rate each other on five personality traits, based entirely on appearance, as they sat for 15 minutes in silence. For three traits—extroversion, conscientiousness and openness—the observers’ rapid judgements matched real personality scores significantly more often than chance. More recently, researchers have re-examined the link between appearance and personality, notably Anthony Little of the University of Stirling and David Perrett of the University of St Andrews, both in the UK. They pointed out that the Michigan studies were not tightly controlled for confounding factors. But when Little and Perrett re-ran the experiment using mugshots rather than live subjects, they also found a link between facial appearance and personality—though only for extroversion and conscientiousness. Little and Perrett claimed that they only found a correlation at the extremes of personality.

Justin Carre and Cheryl McCormick of Brock University in Ontario, Canada studied 90 ice-hockey players. They found that a wider face in which the cheekbone-to-cheekbone distance was unusually large relative to the distance between brow and upper lip was linked in a statistically significant way with the number of penalty minutes a player was given for violent acts including slashing, elbowing, checking from behind and fighting. The kernel of truth idea isn’t the only explanation on offer for our readiness to make facial judgements. Leslie Zebrowitz, a psychologist at Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts, says that in many cases snap judgements are not accurate. The snap judgement, she says, is often an “overgeneralisation” of a more fundamental response. A classic example of overgeneralisation can be seen in predators’ response to eye spots, the conspicuous circular markings seen on some moths, butterflies and fish. These act as a deterrent to predators because they mimic the eyes of other creatures that the potential predators might see as a threat.

Another researcher who leans towards overgeneralisation is Alexander Todorov. With Princeton colleague Nikolaas Oosterhof, he recently put forward a theory which he says explains our snap judgements of faces in terms of how threatening they appear. Todorov and Oosterhof asked people for their gut reactions to pictures of emotionally neutral faces, sifted through all the responses, and boiled them down to two underlying factors: how trustworthy the face looks, and how dominant. Todorov and Oosterhof conclude that personality judgements based on people’s faces are an overgeneralisation of our evolved ability to infer emotions from facial expressions, and hence a person’s intention to cause us harm and their ability to carry it out. Todorov, however, stresses that overgeneralisation does not rule out the idea that there is sometimes a kernel of truth in these assessments of personality.

So if there is a kernel of truth, where does it come from? Perrett has a hunch that the link arises when our prejudices about faces turn into self-fulfilling prophecies—an idea that was investigated by other researchers back in 1977. Our expectations can lead us to influence people to behave in ways that confirm those expectations: consistently treat someone as untrustworthy and they end up behaving that way. This effect sometimes works the other way round, however, especially for those who look cute. The Nobel prize-winning ethologist Konrad Lorenz once suggested that baby-faced features evoke a nurturing response. Support for this has come from work by Zebrowitz, who has found that baby-faced boys and men stimulate an emotional centre of the brain, the amygdala, in a similar way. But there’s a twist. Babyfaced men are, on average, better educated, more assertive and apt to win more military medals than their mature-looking counterparts. They are also more likely to be criminals; think Al Capone. Similarly, Zebrowitz found baby-faced boys to be quarrelsome and hostile, and more likely to be academic highfliers. She calls this the “self-defeating prophecy effect”: a man with a baby face strives to confound expectations and ends up overcompensating.

There is another theory that recalls the old parental warning not to pull faces because they might freeze that way. According to this theory, our personality moulds the way our faces look. It is supported by a study two decades ago which found that angry old people tend to look cross even when asked to strike a neutral expression. A lifetime of scowling, grumpiness and grimaces seemed to have left its mark.

Questions 1-5

Do the following statements agree with the views of the writer in Reading Passage?

In boxes 1-5 on your answer sheet, write

YES if the statement agrees with the views of the writer

NO if the statement contradicts the views of the writer

NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say that the writer thinks about this

1/ Robert Fitzroy’s first impression of Darwin was accurate.

2/ The precise rules of “physiognomy” have remained unchanged since the 18th century.

3/ The first impression of a person can be modified later with little effort.

4/ People who appear capable are more likely to be chosen to a position of power.

5/ It is unfair for good-looking people to be better treated in society

Questions 6-10

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

Write your answers in boxes 6-10 on your answer sheet.

6./ What’s true about Anthony Little and David Perrett’s experiment?

A It is based on the belief that none of the conclusions in the Michigan experiment is accurate.

B It supports parts of the conclusions in the Michigan experiment.

C It replicates the study conditions in the Michigan experiment.

D It has a greater range of faces than in the Michigan experiment.

7./ What can be concluded from Justin Carre and Cheryl McCormick’s experiment?

A A wide-faced man may be more aggressive.

B Aggressive men have a wide range of facial features.

C There is no relation between facial features and an aggressive character.

D It’s necessary for people to be aggressive in competitive games.

8./ What’s exemplified by referring to butterfly marks?

A Threats to safety are easy to notice.

B Instinct does not necessarily lead to accurate judgment.

C People should learn to distinguish between accountable and unaccountable judgments.

D Different species have various ways to notice danger.

9./ What is the aim of Alexander Todorov’s study?

A to determine the correlation between facial features and social development

B to undermine the belief that appearance is important

C to learn the influence of facial features on judgments of a person’s personality

D to study the role of judgments in a person’s relationship

10./ Which of the following is the conclusion of Alexander Todorov’s study?

A People should draw accurate judgments from overgeneralization.

B Using appearance to determine a person’s character is undependable.

C Overgeneralization can be misleading as a way to determine a person’s character.

D The judgment of a person’s character based on appearance may be accurate.

Questions 11-14

Complete each sentence with the correct ending, A-F, below.

Write the correct letter, A-F, in boxes 11-14 on your answer sheet.

11/ Perret believed people behaving dishonestly

12/ The writer supports the view that people with babyish features

13/ According to Zebrowitz, baby-faced people who behave dominantly

14/ The writer believes facial features

A judge other people by overgeneralization,

B may influence the behaviour of other people,

C tend to commit criminal acts.

D may be influenced by the low expectations of other people.

E may show the effect of long-term behaviours.

F may be trying to repel the expectations of other people.