PASSAGE 1 Radio Automation

Today they are everywhere. Production lines controlled by computers and operated by robots. There’s no chatter of assembly workers, just the whirr and click of machines. In the mid-1940s, the workerless factory was still the stuff of science fiction. There were no computers to speak of and electronics was primitive. Yet hidden away in the English countryside was a highly automated production line called ECME, which could turn out 1500 radio receivers a day with almost no help from human hands.

A.

John Sargrove, the visionary engineer who developed the technology, was way ahead of his time. For more than a decade, Sargrove had been trying to figure out how to make cheaper radios. Automating the manufacturing process would help. But radios didn’t lend themselves to such methods: there were too many parts to fit together and too many wires to solder. Even a simple receiver might have 30 separate components and 80 hand-soldered connections. At every stage, things had to be tested and inspected. Making radios required highly skilled labour—and lots of it.

B.

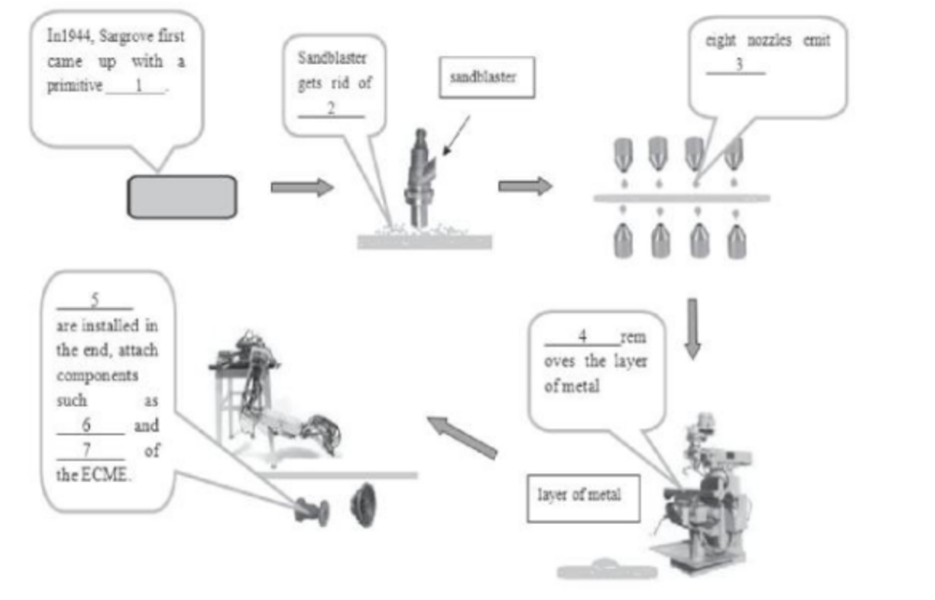

In 1944, Sargrove came up with the answer. His solution was to dispense with most of the fiddly bits by inventing a primitive chip—a slab of Bakelite with all the receiver’s electrical components and connections embedded in it. This was something that could be made by machines, and he designed those too. At the end of the war, Sargrove built an automatic production line, which he called ECME (electronic circuit-making equipment), in a small factory in Effingham, Surrey.

C.

An operator sat at one end of each ECME line, feeding in die plates. She didn’t need much skill, only quick hands. From now on, everything was controlled by electronic switches and relays. First stop was the sandblaster, which roughened the surface of the plastic BO that molten metal would stick to it The plates were then cleaned to remove any traces of grit The machine automatically checked that the surface was rough enough before sending the plate to the spraying section. There, eight nozzles rotated into position and sprayed molten zinc over both sides of the plate. Again, the nozzles only began to spray when a plate was in place. The plate whizzed on. The next stop was the milling machine, which ground away the surface layer of metal to leave the circuit and other components in the grooves and recesses. Now the plate was a composite of metal and plastic. It sped on to be lacquered and have its circuits tested. By the time it emerged from the end of the line, robot hands had fitted it with sockets to attach components such as valves and loudspeakers. When ECME was working flat out; the whole process took 20 seconds.

D.

ECME was astonishingly advanced. Electronic eyes, photocells that generated a small current when a panel arrived, triggered each step in the operation, BO avoiding excessive wear and tear on the machinery. The plates were automatically tested at each stage as they moved along the conveyor. And if more than two plates in succession were duds, the machines were automatically adjusted—or if necessary halted In a conventional factory, I workers would test faulty circuits and repair them. But Sargrove’s assembly line produced circuits so cheaply they just threw away the faulty ones. Sargrove’s circuit board was even more astonishing for the time. It predated the more familiar printed circuit, with wiring printed on aboard, yet was more sophisticated. Its built-in components made it more like a modem chip.

E.

When Sargrove unveiled his invention at a meeting of the British Institution of Radio Engineers in February 1947, the assembled engineers were impressed. So was the man from The Times. ECME, he reported the following day, “produces almost without human labour, a complete radio receiving set. This new method of production can be equally well applied to television and other forms of electronic apparatus. F. The receivers had many advantages over their predecessors, wit components they were more robust. Robots didn’t make the sorts of mistakes human assembly workers sometimes did. “Wiring mistakes just cannot happen,” wrote Sargrove. No w ừ es also meant the radios were lighter and cheaper to ship abroad. And with no soldered wires to come unstuck, the radios were more reliable. Sargrove pointed out that the drcuit boards didn’t have to be flat. They could be curved, opening up the prospect of building the electronics into the cabinet of Bakelite radios.

G.

Sargrove was all for introducing this type of automation to other products. It could be used to make more complex electronic equipment than radios, he argued. And even if only part of a manufacturing process were automated, the savings would be substantial. But while his invention was brilliant, his timing was bad. ECME was too advanced for its own good. It was only competitive on huge production runs because each new job meant retooling the machines. But disruption was frequent. Sophisticated as it was, ECME still depended on old- fashioned electromechanical relays and valves—which failed with monotonous regularity. The state of Britain’s economy added to Sargrove’s troubles. Production was dogged by power cuts and post-war shortages of materials. Sargrove’s financial backers began to get cold feet.

H.

There was another problem Sargrove hadn’t foreseen. One of ECME’s biggest advantages—the savings on the cost of labour—also accelerated its downfall. Sargrove’s factory had two ECME production lines to produce the two c ữ cuits needed for each radio. Between them these did what a thousand assembly workers would otherwise have done. Human hands were needed only to feed the raw material in at one end and plug the valves into then sockets and fit the loudspeakers at the other. After that, the only job left was to fit the pair of Bakelite panels into a radio cabinet and check that it worked.

I.

Sargrove saw automation as the way to solve post-war labour shortages. With somewhat Utopian idealism, he imagined his new technology would free people from boring, repetitive jobs on the production line and allow them to do more interesting work. “Don’t get the idea that we are out to rob people of then jobs,” he told the Daily Mnror. “Our task is to liberate men and women from being slaves of machines.”

J.

The workers saw things differently. They viewed automation in the same light as the everlasting light bulb or the suit that never wears out—as a threat to people’s livelihoods. If automation spread, they wouldn’t be released to do more exciting jobs. They’d be released to join the dole queue. Financial backing for ECME fizzled out. The money dried up. And Britain lost its lead in a technology that would transform industry just a few years later.

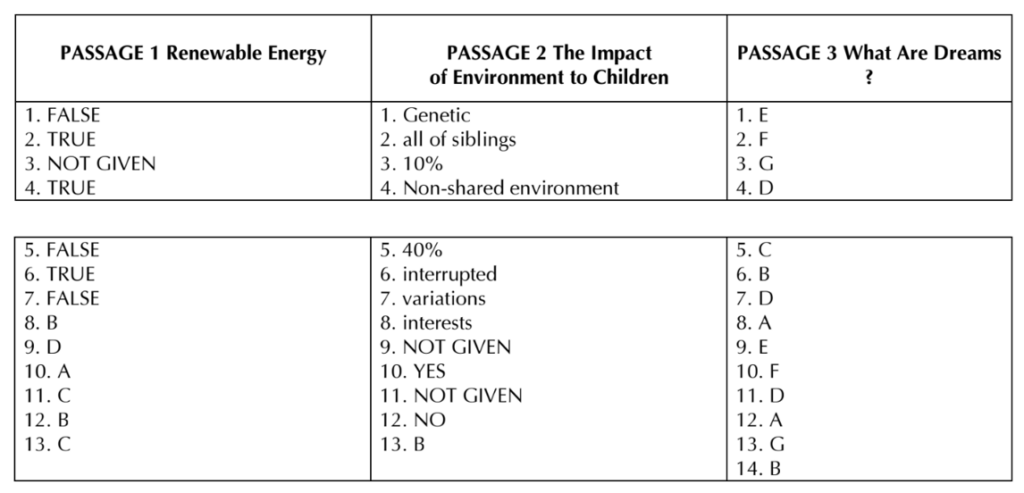

Questions 8-11

Complete the following summary of the paragraphs of Reading Passage. using NO more than two words from the

Reading Passage for each answer. Writs your answers inboxes 8-11 on your answer sheet

Summary

Sargrove had been dedicated to create a 8 ………………….. radio by automation of manufacture. The old version of radio had a large number of independent 9………………….. . After this innovation made, wireless-

style radios became 10 ………………….. and inexpensive to export oversea. As the Saigrove saw it, the real benefit of ECME’s radio was that it reduced 11 ………………….. of manual work; which can be easily copied to other industries of manufacturing electronic devices.

Questions 12-13

Choose the correct letter A, B, C or D.

Write your answers inboxes 12-13 on your answer sheet

12./ What were workers attitude towards ECME Model initialy

A anxious

B welcoming

C boring

D inspiring

13./ What is the main idea of this passage?

A approach to reduce the price of radio

B a new generation of fully popular products and successful business

C in application of die automation in the early stage

D ECME technology can be applied in many product fields

PASSAGE 2 How do we find our way?

A.

Most modern navigation, such as the Global Positioning System (GPS), relies primarily on positions determined electronically by receivers collecting information from satellites. Yet if the satellite service’s digital maps become even slightly outdated, we can become lost. Then we have to rely on the ancient human skill of navigating in three dimensional space. Luckily, our biological finder has an important advantage over GPS: we can ask questions of people on the sidewalk, or follow a street that looks familiar, or rely on a navigational rubric. The human positioning system is flexible and capable of learning. Anyone who knows the way from point A to point B-and from A to C-can probably figure out how to get from B to C, too.

B.

But how does this complex cognitive system really work? Researchers are looking at several strategies people use to orient themselves in space: guidance, path integration and route following. We may use all three or combinations thereof, and as experts learn more about these navigational skills, they are making the case that our abilities may underlie our powers of memory and logical thinking. For example, you come to New York City for the first time and you get off the train at Grand Central Terminal in midtown Manhattan. You have a few hours to see popular spots you have been told about: Rockefeller Center, Central Park, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. You meander in and out of shops along the way. Suddenly, it is time to get back to the station. But how?

C.

If you ask passersby for help, most likely you will receive information in many different forms. A person who orients herself by a prominent landmark would gesture southward: “Look down there. See the tall, broad MetLife Building? Head for that- the station is right below it.” Neurologists call this navigational approach “guidance”, meaning that a landmark visible from a distance serves as the marker for one’s destination.

D.

Another city dweller might say: “What places do you remember passing? … Okay. Go toward the end of Central Park, then walk down to St. Patrick’s Cathedral. A few more blocks, and Grand Central will be off to your left.” In this case, you are pointed toward the most recent place you recall, and you aim for it. Once there you head for the next notable place and so on, retracing your path. Your brain is adding together the individual legs of your trek into a cumulative progress report. Researchers call this strategy “path integration.” Many animals rely primarily on path integration to get around, including insects, spiders, crabs and rodents. The desert ants of the genus Cataglyphis employ this method to return from foraging as far as 100 yards away. They note the general direction they came from and retrace their steps, using the polarization of sunlight to orient themselves even under overcast skies. On their way back they are faithful to this inner homing vector. Even when a scientist picks up an ant and puts it in a totally different spot, the insect stubbornly proceeds in the originally determined direction until it has gone “back” all of the distance it wandered from its nest. Only then does the ant realize it has not succeeded, and it begins to walk in successively larger loops to find its way home.

E.

Whether it is trying to get back to the anthill or the train station, any animal using path integration must keep track of its own movements so it knows, while returning, which segments it has already completed. As you move, your brain gathers data from your environment-sights, sounds, smells, lighting, muscle contractions, a sense of time passing-to determine which way your body has gone. The church spire, the sizzling sausages on that vendor’s grill, the open courtyard, and the train station-all represent snapshots of memorable junctures during your journey.

F.

In addition to guidance and path integration, we use a third method for finding our way. An office worker you approach for help on a Manhattan street comer might say: “Walk straight down Fifth, turn left on 47th, turn right on Park, go through the walkway under the Helmsley Building, then cross the street to the MetLife Building into Grand Central.” This strategy, called route following, uses landmarks such as buildings and street names, plus directions straight, turn, go through—for reaching intermediate points. Route following is more precise than guidance or path integration, but if you forget the details and take a wrong turn, the only way to recover is to backtrack until you reach a familiar spot, because you do not know the general direction or have a reference landmark for your goal. The route following navigation strategy truly challenges the brain. We have to keep all the landmarks and intermediate directions in our head. It is the most detailed and therefore most reliable method, but it can be undone by routine memory lapses. With path integration, our cognitive memory is less burdened; it has to deal with only a few general instructions and the homing vector. Path integration works because it relies most fundamentally on our knowledge of our body’s general direction of movement, and we always have access to these inputs. Nevertheless, people often choose to give route-following directions, in part because saying “Go straight that way!” just does not work in our complex, man made surroundings.

G.

Road Map or Metaphor? On your next visit to Manhattan you will rely on your memory to get present geographic information for convenient visual obviously seductive: maps around. Most likely you will use guidance, path integration and route following in various combinations. But how exactly do these constructs deliver concrete directions? Do we humans have, as an image of the real world, a kind of road map in our heads? Neurobiologists and cognitive psychologists do call the portion of our memory that controls navigation a “cognitive map”. The map metaphor is are the easiest way to inspection. Yet the notion of a literal map in our heads may be misleading; a growing body of research implies that the cognitive map is mostly a metaphor. It may be more like a hierarchical structure of relationships.

Questions 1-5

Use the information in the passage to match the category of each navigation method (listed A-C) with correct statement.

Write the appropriate letters A-C in boxes 1-5 on your answer sheet.

NB You may use any letter more than once.

A. guidance method

B. path integration method

C. route following method

1/ Split the route up into several smaller parts.

2/ When mistakes are made, a person needs to go back.

3/ Find a building that can be seen from far away.

4/ Recall all the details along the way.

5/ Memorize the buildings that you have passed by.

Questions 6-8

6./ According to the passage, how does the Cataglyphis ant respond if it is taken to a different location?

A changes its orientation sensors to adapt

B releases biological scent for help from others

C continues to move according to the original orientation

D gets completely lost once disturbed

7./ What did the author say about the route following method?

A dependent on directions to move on

B dependent on memory and reasoning

C dependent on man-made settings

D dependent on the homing vector

8./ Which of the following is true about the “cognitive map” in this passage?

A There is no obvious difference between it and a real map.

B It exists in our heads and is always correct.

C It only exists in some cultures.

D It is managed by a portion of our memory.

Questions 9-13

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage?

In boxes 9-13 on your answer sheet, write

TRUE

FALSE

NOT GIVEN

if the statement agrees with the information

if the statement contradicts the information

if there is no information on this

9/ Biological navigation is flexible.

10/ Insects have many ways to navigate that are in common with many other animals.

11/ When someone follows a route, he or she collects comprehensive perceptual information in the mind along the way.

12/ The path integration method has a higher requirement of memory compared with the route following method.

13/ When people find their way, they have an exact map in their mind.

PASSAGE 3 Art in Iron and Steel

A

Works of engineering and technology are sometimes viewed as the antitheses of art and humanity. Think of the connotations of assembly lines, robots, and computers. Any positive values there might be in such creations of the mind and human industry can be overwhelmed by the associated negative images of repetitive, stressful, and threatened jobs. Such images fuel the arguments of critics of technology even as they may drive powerful cars and use the Internet to protest what they see as the artless and dehumanizing aspects of living in an industrialized and digitized society. At the same time, landmark megastructures such as the Brooklyn and Golden Gate bridges are almost universally hailed as majestic human achievements as well as great engineering monuments that have come to embody the spirits of their respective cities. The relationship between art and engineering has seldom been easy or consistent.

B

The human worker may have appeared to be but a cog in the wheel of industry, yet photographers could reveal the beauty of line and composition in a worker doing something as common as using a wrench to turn a bolt. When Henry Ford’s enormous River Rouge plant opened in 1927 to produce the Model A, the painter/photographer Charles Sheeler was chosen to photograph it. The world’s largest car factory captured the imagination of Sheeler, who described it as the most thrilling subject he ever had to work with. The artist also composed oil paintings of the plant, giving them titles such as American Landscape and Classic Landscape.

C

Long before Sheeler, other artists, too, had seen the beauty and humanity in works of engineering and technology. This is perhaps no more evident than in Coalbrookdale, England, where iron, which was so important to the industrial revolution, was worked for centuries. Here, in the late eighteenth century, Abraham Darby III cast on the banks of the Severn River the large ribs that formed the world’s first iron bridge, a dramatic departure from the classic stone and timber bridges that dotted the countryside and were captured in numerous serene landscape paintings. The metal structure, simply but appropriately called Iron Bridge, still spans the river and still beckons engineers, artists, and tourists to gaze upon and walk across it, as if on a pilgrimage to a revered place.

D

At Coalbrookdale, the reflection of the ironwork in the water completes the semicircular structure to form a wide-open eye into the future that is now the past. One artist’s bucolic depiction shows pedestrians and horsemen on the bridge, as if on a woodland trail. On one shore, a pair of well-dressed onlookers interrupts their stroll along the riverbank, perhaps to admire the bridge. On the other side of the gently flowing river, a lone man leads two mules beneath an arch that lets the towpath pass through the bridge’s abutment. A single boatman paddles across the river in a tiny tub boat. He is in no rush because there is no towline to carry from one side of the bridge to the other. This is how Michael Rooker was Iron Bridge in his 1792 painting. A colored engraving of the scene hangs in the nearby Coalbrookdale museum, along with countless other contemporary renderings of the bridge in its full glory and in its context, showing the iron structure not as a blight on the landscape but at the center of it. The surrounding area at the same time radiates out from the bridge and pales behind it.

E

In the nineteenth century, the railroads captured the imagination of artists, and the steam engine in the distance of a landscape became as much a part of it as the herd of cows in the foreground. The Impressionist Claude Monet painted man-made structures like railway stations and cathedrals as well as water lilies. Portrait painters such as Christian Schussele found subjects in engineers and inventors – and their inventions – as well as in the American founding fathers. By the twentieth century, engineering, technology, and industry were very well established as subjects for artists.

F

American-born Joseph Pennell illustrated many European travel articles and books. Pennell, who early in his career made drawings of buildings under construction and shrouded in scaffolding, returned to America late in life and recorded industrial activities during World War I. He is perhaps best known among engineers for his depiction of the Panama Canal as it neared completion and his etchings of the partially completed Hell Gate and Delaware River bridges.

G

Pennell has often been quoted as saying, “Great engineering is great art,” a sentiment that he expressed repeatedly. He wrote of his contemporaries, “I understand nothing of engineering, but I know that engineers are the greatest architects and the most pictorial builders since the Greeks.” Where some observers saw only utility, Pennell saw also beauty, if not in form then at least in scale. He felt he was not only rendering a concrete subject but also conveying through his drawings the impression that it made on him. Pennell called the sensation that he felt before a great construction project ‘The Wonder of Work”. He saw engineering as a process. That process is memorialized in every completed dam, skyscraper, bridge, or other great achievement of engineering.

H

If Pennell experienced the wonder of work in the aggregate, Lewis Hine focused on the individuals who engaged in the work. Hine was trained as a sociologist but became best known as a photographer who exposed the exploitation of children. His early work documented immigrants passing through Ellis Island, along with the conditions in the New York tenements where they lived and the sweatshops where they worked. Upon returning to New York, he was given the opportunity to record the construction of the Empire State Building, which resulted in the striking photographs that have become such familiar images of daring and insouciance. He put his own life at risk to capture workers suspended on cables hundreds of feet in the air and sitting on a high girder eating lunch. To engineers today, one of the most striking features of these photos, published in 1932 in Men at Work, is the absence of safety lines and hard hats. However, perhaps more than anything, the photos evoke Pennell’s “The Wonder of Work” and inspire admiration for the bravery and skill that bring a great engineering project to completion.

Questions 1-5 The Reading Passage has eight paragraphs A-H. Which paragraph contains the following information?

Write the correct letter A-H, in boxes 1-5 on your answer sheet.

1/ Art connected with architecture for the first time.

2/ small artistic object and constructions built are put together

3 /the working condition were recorded by the artist as an exciting subject.

4/ mention of one engineers’ artistic work on an unfinished engineering project

5/ Two examples of famous bridges which became the iconic symbols of those cities

Questions 6-10

Use the information in the passage to match the people (listed A-F) with opinions or deeds below.

Write the appropriate letters A-F in boxes 6-10 on your answer sheet.

List of people

A Charles Sheeler

B Michael Rooker

C Claude Monet

D Christian Schussele

E Joseph Pennell

F Lewis Hine

6/ who made a comment that concrete constructions have a beauty just as artistic processes created by engineers the architects

7/ who made a romantic depiction of an old bridge in one painting

8/ who produced art pieces demonstrating the courage of workers in the site

9/ who produced portraits involving subjects in engineers and inventions and historical human heroes.

10/ who produced a painting of factories and named them ambitiously

Questions 11-14

Complete the following summary of the paragraphs of Reading Passage

Using NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the Reading Passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 11-14 on your answer sheet.

Iron bridge Coalbrookdale, England

In the late eighteenth century, as artists began to capture the artistic attractiveness incorporated into architecture via engineering and technology were captured in numerous serene landscape paintings. One good example, the engineer called 11 had designed the first iron bridge in the world and changed to using irons yet earlier bridges in the countryside were constructed using materials such as 12 and wood. This first Iron bridge which across the 13 was much significant in the industrial revolution period and it functioned for centuries. Numerous spectacular paintings and sculpture of Iron Bridge are collected and exhibited locally in 14 , showing the iron structure as a theme on the landscape.