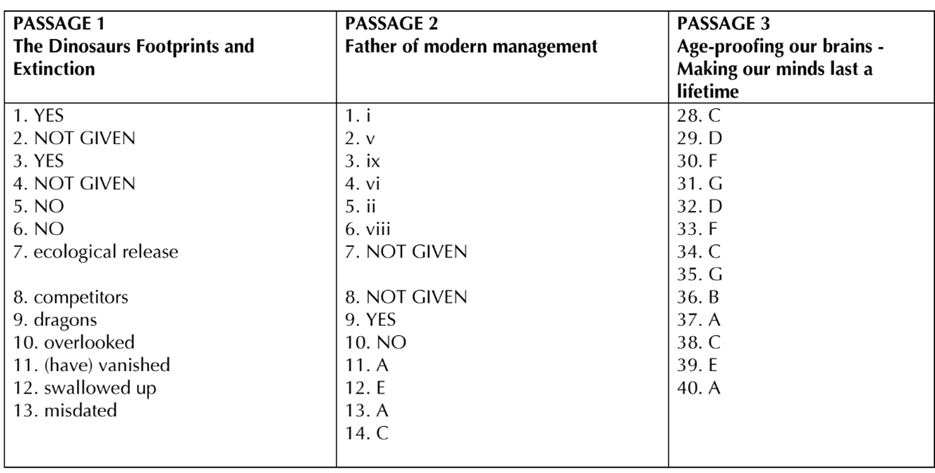

PASSAGE 1 The Dinosaurs Footprints and Extinction

A

EVERYBODY knows that the dinosaurs were killed by an asteroid. Something big hit the earth 65 million years ago and, when the dust had fallen, so had the great reptiles. There is thus a nice if ironic, symmetry in the idea that a similar impact brought about the dinosaurs’ rise. That is the thesis proposed by Paul Olsen, of Columbia University, and his colleagues in this week’s Science.

B

Dinosaurs first appeared in the fossil record 230m years ago, during the Triassic period. But they were mostly small, and they shared the earth with lots of other sorts of reptile. It was in the subsequent Jurassic, which began 202 million years ago, that they overran the planet and turned into the monsters depicted in the book and movie “Jurassic Park”. (Actually, though, the dinosaurs that appeared on screen were from the still more recent Cretaceous period.) Dr Olsen and his colleagues are not the first to suggest that the dinosaurs inherited the earth as the result of an asteroid strike. But they are the first to show that the takeover did, indeed, happen in a geological eyeblink.

C

Dinosaur skeletons are rare. Dinosaur footprints are, however, surprisingly abundant. And the sizes of the prints are as good an indication of the sizes of the beasts as are the skeletons themselves. Dr Olsen and his colleagues, therefore, concentrated on prints, not bones.

D

The prints in question were made in eastern North America, a part of the world the full of rift valleys to those in East Africa today. Like the modern African rift valleys, the Triassic/Jurassic American ones contained lakes, and these lakes grew and shrank at regular intervals because of climatic changes caused by periodic shifts in the earth’s orbit. (A similar phenomenon is responsible for modern ice ages.) That regularity, combined with reversals in the earth’s magnetic field, which are detectable in the tiny fields of certain magnetic minerals, means that rocks from this place and period can be dated to within a few thousand years. As a bonus, squishy lake-edge sediments are just the things for recording the tracks of passing animals. By dividing the labour between themselves, the ten authors of the paper were able to study such tracks at 80 sites.

E

The researchers looked at 18 so-called ichnotaxa. These are recognizable types of the footprint that cannot be matched precisely with the species of animal that left them. But they can be matched with a general sort of animal, and thus act as an indicator of the fate of that group, even when there are no bones to tell the story. Five of the ichnotaxa disappear before the end of the Triassic, and four march confidently across the boundary into the Jurassic. Six, however, vanish at the boundary, or only just splutter across it; and there appear from nowhere, almost as soon as the Jurassic begins.

F

That boundary itself is suggestive. The first geological indication of the impact that killed the dinosaurs was an unusually high level of iridium in rocks at the end of the Cretaceous when the beasts disappear from the fossil record. Iridium is normally rare at the earth’s surface, but it is more abundant in meteorites. When people began to believe the impact theory, they started looking for other Cretaceous-and anomalies. One that turned up was a surprising abundance of fern spores in rocks just above the boundary layer – a phenomenon known as a “fern spike”.

G

That matched the theory nicely. Many modern ferns are opportunists. They cannot compete against plants with leaves, but if a piece of land is cleared by, say, a volcanic eruption, they are often the first things to set up shop there. An asteroid strike would have scoured much of the earth of its vegetable cover, and provided a paradise for ferns. A fern spike in the rocks is thus a good indication that something terrible has happened.

H

Both an iridium anomaly and a fern spike appear in rocks at the end of the Triassic, too. That accounts for the disappearing ichnotaxa: the creatures that made them did not survive the holocaust. The surprise is how rapidly the new ichnotaxa appear.

I

Dr Olsen and his colleagues suggest that the explanation for this rapid increase in size may be a phenomenon called ecological release. This is seen today when reptiles (which, in modern times, tend to be small creatures) reach islands where they face no competitors. The most spectacular example is on the Indonesian island of Komodo, where local lizards have grown so large that they are often referred to as dragons. The dinosaurs, in other words, could flourish only when the competition had been knocked out.

J

That leaves the question of where the impact happened. No large hole in the earth’s crust seems to be 202m years old. It may, of course, have been overlooked. Old craters are eroded and buried, and not always easy to find. Alternatively, it may have vanished. Although the continental crust is more or less permanent, the ocean floor is constantly recycled by the tectonic processes that bring about continental drift. There is no ocean floor left that is more than 200m years old, so a crater that formed in the ocean would have been swallowed up by now.

K

There is a third possibility, however. This is that the crater is known, but has been misdated. The Manicouagan “structure”, a crater in Quebec, is thought to be 214m years old. It is huge – some 100km across – and seems to be the largest of between three and five craters that formed within a few hours of each other as the lumps of a disintegrated comet hit the earth one by one.

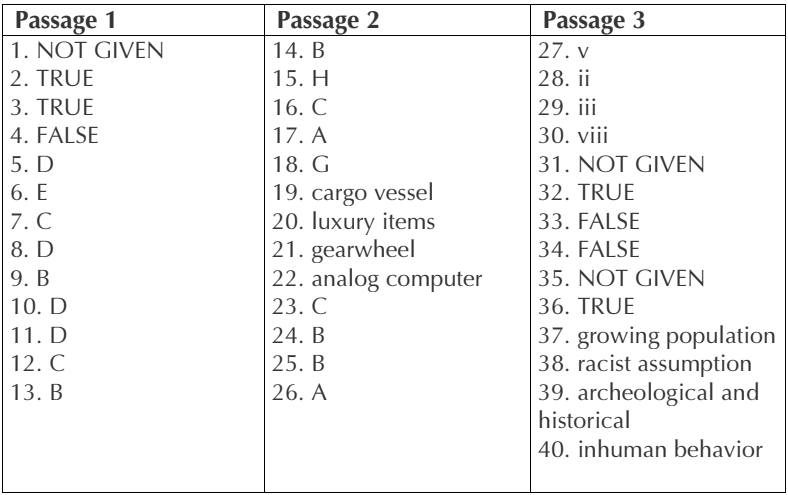

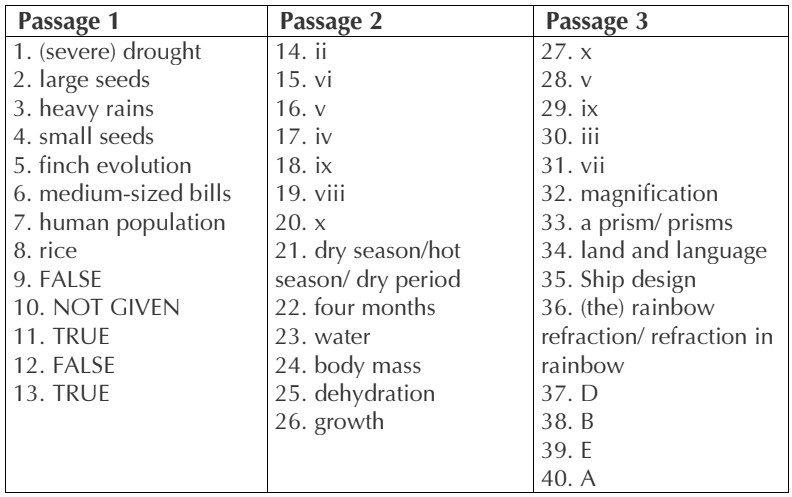

Questions 1-6

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 1? In boxes 1-6 on your answer sheet, write

YES if the statement is true

NO if the statement is false

NOT GIVEN if the information is not given in the passage

1/ Dr Paul Olsen and his colleagues believe that asteroid knock may also lead to dinosaurs’ boom.

2/ Books and movie like Jurassic Park often exaggerate the size of the dinosaurs.

3 /Dinosaur footprints are more adequate than dinosaur skeletons.

4/ The prints were chosen by Dr Olsen to study because they are more detectable than the earth magnetic field to track the date of geological precise within thousands of years.

5/ Ichnotaxa showed that footprints of dinosaurs offer exact information of the trace left by an individual species.

6 We can find more Iridium in the earth’s surface than in meteorites.

Questions 7-13 Complete the following summary of the paragraphs of Reading Passage . Using NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the Reading Passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 7-13 on your answer sheet.

Dr Olsen and his colleagues applied a phenomenon named 7 ……………………to explain the large size of the Eubrontes, which is a similar case to that nowadays reptiles invade a place where there are no 8 …………………… for example, on an island called Komodo, indigenous huge lizards grow so big that people even regarding them as 9 …………………… However, there were no old impact trace being found? The answer may be that we have 10 …………………… . the evidence. Old craters are difficult to spot or it probably 11 …………………… Due to the effect of the earth moving. Even a crater formed in Ocean had been 12 ……………………under the impact of crust movement. Besides, the third hypothesis is that the potential evidence some craters maybe 13 ……………………

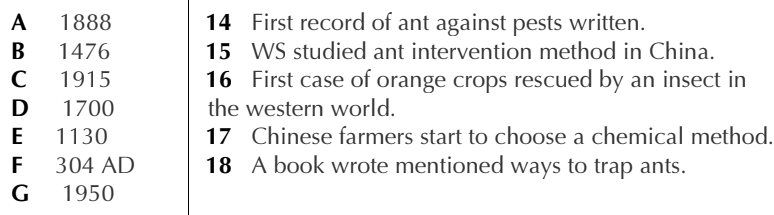

PASSAGE 2 Father of modern management

A

Peter Drucker was one of the most important management thinkers of the past hundred years. He wrote about 40 book and thousands of articles and he never rested in his mission to persuade the world that management matters. “Management is an organ of institutions … the organ that converts a mob into an organisation, and human efforts into performance.” Did he succeed? The range of his influence was extraordinary. Wherever people grapple with tricky management problems, from big organizations to small ones, from the public sector to the private, and increasingly in the voluntary sector, you can find Drucker’s fingerprints.

B

His first two books – The End of Economic Man (1939) and The Future of Industrial Man (1942) – had their admirers, including Winston Churchill, but they annoyed academic critics by ranging so widely over so many different subjects. Still, the second of these books attracted attention with its passionate insistence that companies had a social dimension as well as an economic purpose. His third book, The Concept of the Corporation, became an instant bestseller and has remained in print ever since.

C

The two most interesting arguments in The Concept of the Corporation actually had little to do with the decentralization fad. They were to dominate his work. The first had to do with “empowering” workers. Drucker believed in treating workers as resources rather than just as costs. He was a harsh critic of the assembly-line system of production that then dominated the manufacturing sector – partly because assembly lines moved at the speed of the slowest and partly because they failed to engage the creativity of individual workers. The second argument had to do with the rise of knowledge workers. Drucker argued that the world is moving from an “economy of goods” to an economy of “knowledge” – and from a society dominated by an industrial proletariat to one dominated by brain workers. He insisted that this had profound implications for both managers and politicians. Managers had to stop treating workers like cogs in a huge inhuman machine and start treating them as brain workers. In turn, politicians had to realise that knowledge, and hence education, was the single most important resource for any advanced society. Yet Drucker also thought that this economy had implications for knowledge workers themselves. They had to come to terms with the fact that they were neither “bosses” nor “workers”, but something in between: entrepreneurs who had responsibility for developing their most important resource, brainpower, and who also needed to take more control of their own careers, including their pension plans.

D

However, there was also a hard side to his work. Drucker was responsible for inventing one of the rational school of management’s most successful products – “management by objectives”. In one of his most substantial works, The Practice of Management (1954), he emphasised the importance of managers and corporations setting clear long-term objectives and then translating those long-term objectives into more immediate goals. He argued that firms should have an elite corps of general managers, who set these long-term objectives, and then a group of more specialised managers. For his critics, this was a retreat from his earlier emphasis on the soft side of management. For Drucker it was all perfectly consistent: if you rely too much on empowerment you risk anarchy, whereas if you rely too much on command-and-control you sacrifice creativity. The trick is for managers to set long-term goals, but then allow their employees to work out ways of achieving those goals. If Drucker helped make management a global industry, he also helped push it beyond its business base. He was emphatically a management thinker, not just a business one. He believed that management is “the defining organ of all modern institutions”, not just corporations.

E

There are three persistent criticisms of Drucker’s work. The first is that he focused on big organisations rather than small ones. The Concept of the Corporation was in many ways a fanfare to big organisations. As Drucker said, “We know today that in modern industrial production, particularly in modern mass production, the small unit is not only inefficient, it cannot produce at all.” The book helped to launch the “big organisation boom” that dominated business thinking for the next 20 years. The second criticism is that Drucker’s enthusiasm for management by objectives helped to lead the business down a dead end. They prefer to allow ideas, including ideas for long-term strategies, to bubble up from the bottom and middle of the organisations rather than being imposed from on high. Thirdly, Drucker is criticised for being a maverick who has increasingly been left behind by the increasing rigour of his chosen field. There is no single area of academic management theory that he made his own.

F

There is some truth in the first two arguments. Drucker never wrote anything as good as The Concept of the Corporation on entrepreneurial start-ups. Drucker’s work on management by objectives sits uneasily with his earlier and later writings on the importance of knowledge workers and self-directed teams. But the third argument is short-sighted and unfair because it ignores Drucker’s pioneering role in creating the modern profession of management. He produced one of the first systematic studies of a big company. He pioneered the idea that ideas can help galvanise companies. The biggest problem with evaluating Drucker’s influence is that so many of his ideas have passed into conventional wisdom. In other words, he is the victim of his own success. His writings on the importance of knowledge workers and empowerment may sound a little banal today. But they certainly weren’t banal when he first dreamed them up in the 1940s, or when they were first put in to practice in the Anglo-Saxon world in the 1980s. Moreover, Drucker continued to produce new ideas up until his 90s. His work on the management of voluntary organisations remained at the cutting edge.

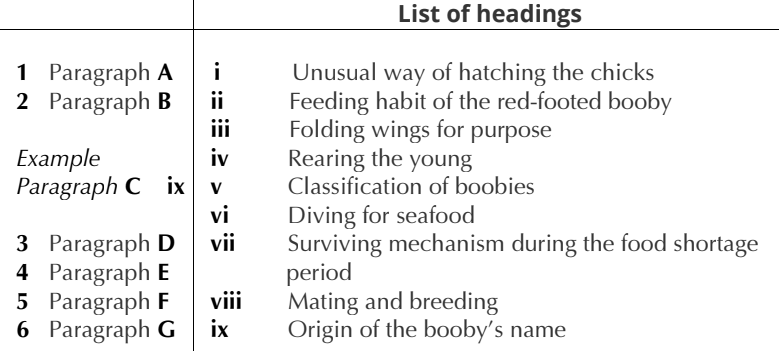

Questions 1-6

Reading Passage has six paragraphs, A-F

Choose the correct heading for each paragraph from the list below.

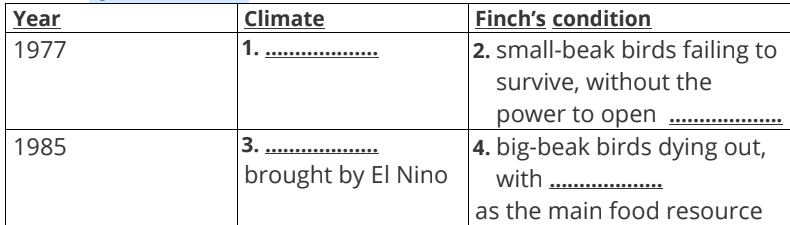

Write the correct number, i-ix, in boxes 1-6 on your answer sheet.

i The popularity and impact of Drucker’s work

ii Finding fault with Drucker

iii The impact of economic globalisation

iv Government regulation of business

v Early publications of Drucker’s

vi Drucker’s view of balanced management

vii Drucker’s rejection of big business

viii An appreciation of the pros and cons of Drucker’s work

ix The changing role of the employee

1/ Paragraph A

2/ Paragraph B

3/ Paragraph C

4/ Paragraph D

5/ Paragraph E

6/ Paragraph F

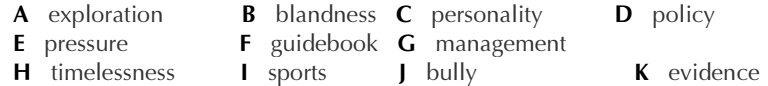

Questions 7-10 Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 2? In boxes 7- 10 on your answer sheet, write

YES if the statement agrees with what is stated in the passage

NO if the statement counters to what is stated in the passage

NOT GIVEN if there is no relevant information given in the passage

7/ Drucker believed the employees should enjoy the same status as the employers in a company

8/ Drucker argued the managers and politicians will dominate the economy during a social transition

9/ Drucker support that workers are not simply put themselves just in the employment relationship and should develop their resources of intelligence voluntarily

10/ Drucker’s work on the management is out of date in moderns days

Questions 11-12 Choose TWO letters from A-E. Write your answers in boxes 12 and 13 on your answer sheet.

Which TWO of the following are true of Drucker’s views?

A High-rank executives and workers should be put in balanced positions in management practice

B Young executives should be given chances to start from low-level jobs

C More emphasis should be laid on fostering the development of the union.

D Management should facilitate workers with tools of self-appraisal instead of controlling them from the

outside force

E Leaders should go beyond the scope of management details and strategically establish goals

Questions 13-14 Choose TWO letters from A-E. Write your answers in boxes 13 and 14 on your answer sheet.

Which TWO of the following are mentioned in the passage as criticisms to Drucker and his views?

A His lectures focus too much on big organisations and ignore the small ones.

B His lectures are too broad and lack of being precise and accurate about the facts.

C He put a source of objectives more on corporate executives but not on average workers.

D He acted much like a maverick and did not set up his own management groups

E He was overstatin

PASSAGE 3 Age-proofing our brains – Making our minds last a lifetime

{A} While it may not be possible to completely age-proof our brains, a brave new world of anti-aging research shows that our gray matter may be far more flexible than we thought. So no one, no matter how old, has to lose their mind. The brain has often been called the three-pound universe. It’s our most powerful and mysterious organ, the seat of the self, laced with as many billions of neurons as the galaxy has stars. No wonder the mere notion of an aging, failing brain–and the prospect of memory loss, confusion, and the unraveling of our personality–is so terrifying. As Mark Williams, M.D., author of The American Geriatrics Society’s Complete Guide to Aging and Health, says, “The fear of dementia is stronger than the fear of death itself.” Yet the degeneration of the brain is far from inevitable. “Its design features are such that it should continue to function for a lifetime,” says Zaven Khachaturian, Ph.D., director of the Alzheimer’s Association’s Ronald and Nancy Reagan Research Institute. “There’s no reason to expect it to deteriorate with age, even though many of us are living longer lives.” In fact, scientists’ view of the brain’s potential is rapidly changing, according to Stanford University neuroscientist Robert Sapolsky, Ph.D. “Thirty-five years ago we thought Alzheimer’s disease was a dramatic version of normal aging . Now we realize it’s a disease with a distinct pathology. In fact, some people simply don’t experience any mental decline, so we’ve begun to study them.’ Antonio Damasio, M.D., Ph.D., head of the Department of Neurology at the University of Iowa and author of Descartes’ Error, concurs. “Older people can continue to have extremely rich and healthy mental lives.’

{B} The seniors were tested in 1988 and again in 1991. Four factors were found to be related to their mental fitness: levels of education and physical activity, lung function, and feelings of self-efficacy. “Each of these elements alters the way our brain functions,” says Marilyn Albert, Ph.D., of Harvard Medical School, and colleagues from Yale, Duke, and Brandeis Universities and the Mt. Sinai School of Medicine, who hypothesizes that regular exercise may actually stimulate blood flow to the brain and nerve growth, both of which create more densely branched neurons rendering the neurons stronger and better able to resist disease. Moderate aerobic exercise, including long brisk walks and frequently climbing stairs, will accomplish this.

{C} Education also seems to enhance brain function. People who have challenged themselves with at least a college education may actually stimulate the neurons in their brains. Moreover, native intelligence may protect our brains. It’s possible that smart people begin life with a greater number of neurons, and therefore have a greater reserve to fall back on if some begin to fail. “If you have a lot of neurons and keep them busy, you may be able to tolerate more damage to your brain before it shows,’ says Peter Davies, M.D., of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, New York, Early linguistic ability also seems to help our brains later in life. A recent study in the New England Journal of Medicine looked at 93 elderly nuns and examined the autobiographies they had written 60 years earlier, just as they were joining a convent The nuns whose essays were complex and dense with ideas remained sharp into their eighties and nineties.

{D} Finally, personality seems to play an important role in protecting our mental prowess. A sense of self-efficacy may protect our brain, buffeting it from the harmful effects of stress. According to Albert, there’s evidence that elevated levels of stress hormones may harm brain cells and cause the hippocampus–a small seahorse-shaped organ that’s a crucial moderator of memory–to atrophy. A sense that we can effectively chart our own course in the world may retard the release of stress hormones and protect us as we age. “It’s not a matter of whether you experience stress or not,’ Albert concludes, “it’s your attitude toward it.” Reducing stress by meditating on a regular basis may buffer the brain as well. It also increases the activity of the brain’s pineal gland , the source of the antioxidant hormone melatonin, which regulates sleep and may retard the aging process. Studies at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center and the University of Western Ontario found that people who meditated regularly had higher levels of melatonin than those who took 5-milligram supplements. Another study, conducted jointly by Maharishi International University, Harvard University, and the University of Maryland, found that seniors who meditated for three months experienced dramatic improvements in their psychological well-being, compared to their non-meditative peers.

{E} Animal studies confirm that both mental and physical activity boost brain fitness. At the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology in Urbana, Illinois, psychologist William Greenough, Ph.D., let some rats play with a profusion of toys. These rodents developed about 25 percent more connections between their neurons than did rats that didn’t get any mentally stimulating recreation. In addition, rats that exercised on a treadmill developed more capillaries in specific parts of their brains than did their sedentary counterparts. This increased the blood flow to their brains. “Clearly the message is to do as many different flyings as possible,” Greenough says.

{F} It’s not just scientists who are catching anti-aging fever. Walk into any health food store, and you’ll find nutritional formulas –with names like Brainstorm and Smart ALEC–that claim to sharpen mental ability. The book Smart Drugs & Nutrients, by Ward Dean, M.D., and John Morgenthaler, was self-published in 1990 and has sold over 120,000 copies worldwide. It has also spawned an underground network of people tweaking their own brain chemistry with nutrients and drugs–the latter sometimes obtained from Europe and Mexico. Sales of ginkgo –an extract from the leaves of the 200-million-year-old ginkgo tree, which has been shown in published studies to increase oxygen in the brain and ameliorate symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease–are up by 22 percent in the last six months alone, according to Paddy Spence, president of SPINS, a San Francisco-based market research firm. Indeed, products that increase and preserve mental performance are a small but emerging segment of the supplements industry, says Linda Gilbert, president of HealthFocus, a company that researches consumer health trends. While neuroscientists like Khachaturian liken the use of these products to the superstition of tossing salt over your shoulder, the public is nevertheless gobbling up nutrients that promise cognitive enhancement.

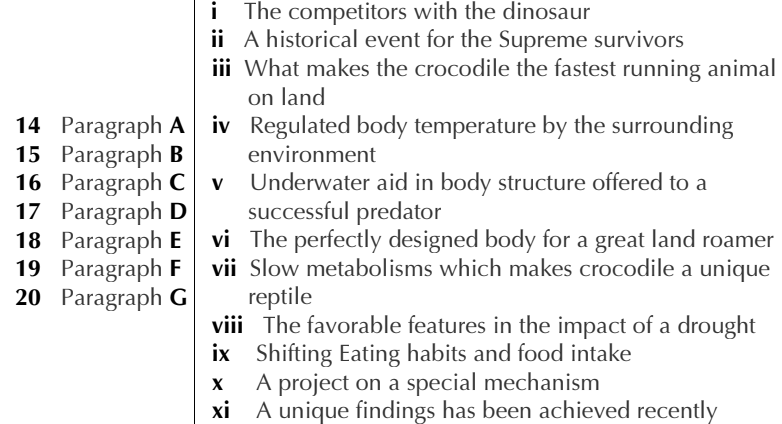

Questions 28-31 Choose the Four correct letters among A-G . Write your answers in boxes 28-31 on your answer sheet. Which of the FOUR situations or conditions assisting the Brains’ function?

(A) Preventive treatment against Alzheimer’s disease

(B) Doing active aerobic exercise and frequently climbing stairs

(C) High levels of education

(D) Early verbal or language competence training

(E) Having more supplements such as ginkgo tree

(F) Participate in more physical activity involving in stimulating tasks

(G) Personality and feelings of self-fulfillment

Questions 32-39

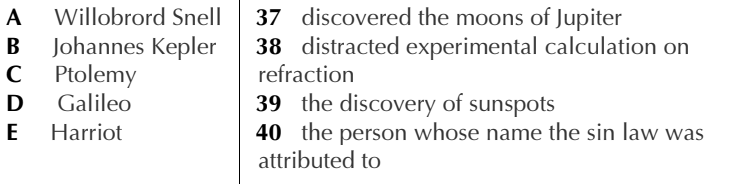

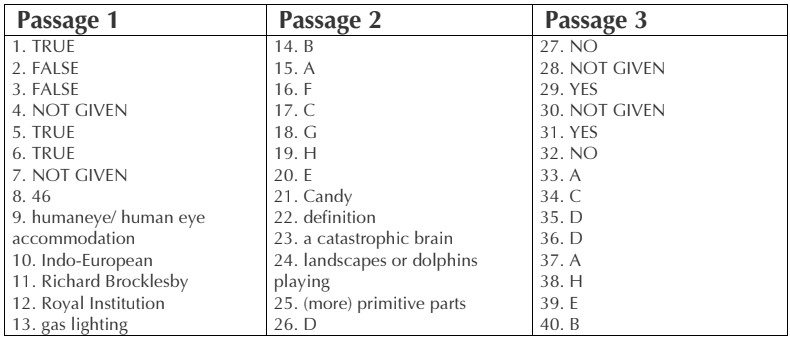

Use the information in the passage to match the people (listed A-G) with opinions or deeds below. Write the appropriate letters A-G in boxes 32-39 on your answer sheet.

NB you may use any latter more than once

(A) Zaven Khachaturian

(B) William Greenough

(C) Marilyn Albert

(D) Robert Sapolsky

(E) Linda Gilbert

(F) Peter Davies

(G) Paddy Spence

(32) Alzheimer’s was probably a kind of disease rather than a normal aging process.

(33) Keeping neurons busy, people may be able to endure more harm to your brain

(34) Regular exercises boost blood flow to the brain and increase anti-disease disability.

(35) Significant increase of Sales of ginkgo has been shown.

(36) More links between their neurons are found among stimulated animals.

(37) Effectiveness of the use of brains supplements products can be of little scientific proof.

(38) Heightened levels of stress may damage brain cells and cause part of brain to deteriorate.

(39) Products that upgrade and preserve mental competence are still a newly developing industry.

Questions 40. Choose the correct letters among A-D Write your answers in box 40 on your answer sheet.

According to the passage, what is the most appropriate title for this passage?

(A) Making our minds last a lifetime

(B) amazing pills of the ginkgo

(C) how to stay healthy in your old hood

(D) more able a brain and neurons