- Passage 1: Video Practice Test!

- Passage 2: Video Practice Test!

- Passage 3: Video Practice Test!

1 – Finches on Islands

A

Today, the quest continues. On Daphne Major-one of the most desolate of the Galápagos Islands, an uninhabited volcanic cone where cacti and shrubs seldom grow higher than a researcher’s knee-Peter and Rosemary Grant have spent more than three decades watching Darwin’s finch respond to the challenges of storms, drought and competition for food Biologists at Princeton University, the Grants know and recognize many of the individual birds on the island and can trace the birds’ lineages hack through time. They have witnessed Darwin’s principle in action again and again, over many generations of finches.

B

The Grants’ most dramatic insights have come from watching the evolving bill of the medium ground finch. The plumage of this sparrow-sized bird ranges from dull brown to jet black. At first glance, it may not seem particularly striking, but among scientists who study evolutionary biology, the medium ground finch is a superstar. Its bill is a middling example in the array of shapes and sizes found among Galápagos finches: heftier than that of the small ground finch, which specializes in eating small, soft seeds, but petite compared to that of the large ground finch, an expert at cracking and devouring big, hard seeds.

C

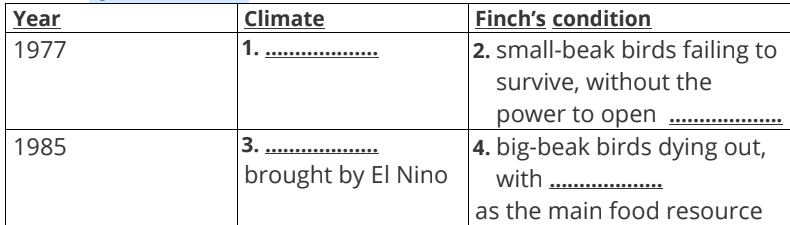

When the Grants began their study in the 1970s, only two species of finch lived on Daphne Major, the medium ground finch and the cactus finch. The island is so small that the researchers were able to count and catalogue every bird. When a severe drought hit in 1977, the birds soon devoured the last of the small, easily eaten seeds. Smaller members of the medium ground finch population, lacking the bill strength to crack large seeds, died out.

D

Bill and body size are inherited traits, and the next generation had a high proportion of big-billed individuals. The Grants had documented natural selection at work-the same process that, over many millennia, directed the evolution of the Galápagos’ 14 unique finch species, all descended from a common ancestor that reached the islands a few million years ago.

E

Eight years later, heavy rains brought by an El Nino transformed the normally meager vegetation on Daphne Major. Vines and other plants that in most years struggle for survival suddenly flourished, choking out the plants that provide large seeds to the finches. Small seeds came to dominate the food supply, and big birds with big bills died out at a higher rate than smaller ones. ‘Natural selection is observable,’ Rosemary Grant says. ‘It happens when the environment changes. When local conditions reverse themselves, so does the direction of adaptation.

F

Recently, the Grants witnessed another form of natural selection acting on the medium ground finch: competition from bigger, stronger cousins. In 1982, a third finch, the large ground finch, came to live on Daphne Major. The stout bills of these birds resemble the business end of a crescent wrench. Their arrival was the first such colonization recorded on the Galápagos in nearly a century of scientific observation. ‘We realized,’ Peter Grant says, ‘we had a very unusual and potentially important event to follow.’ For 20 years, the large ground finch coexisted with the medium ground finch, which shared the supply of large seeds with its bigger-billed relative. Then, in 2002 and 2003, another drought struck. None of the birds nested that year, and many died out. Medium ground finches with large bills, crowded out of feeding areas by the more powerful large ground finches, were hit particularly hard.

G

When wetter weather returned in 2004, and the finches nested again, the new generation of the medium ground finch was dominated by smaller birds with smaller bills, able to survive on smaller seeds. This situation, says Peter Grant, marked the first time that biologists have been able to follow the complete process of an evolutionary change due to competition between species and the strongest response to natural selection that he had seen in 33 years of tracking Galápagos finches.

H

On the inhabited island of Santa Cruz, just south of Daphne Major, Andrew Hendry of McGill University and Jeffrey Podos of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst have discovered a new, man-made twist in finch evolution. Their study focused on birds living near the Academy Bay research station, on the fringe of the town of Puerto Ayora. The human population of the area has been growing fast-from 900 people in 1974 to 9,582 in 2001. Today Puerto Ayora is full of hotels and mai tai bars,’ Hendry says. ‘People have taken this extremely arid place and tried to turn it into a Caribbean resort.’

I

Academy Bay records dating back to the early 1960s show that medium ground finches captured there had either small or large bills. Very few of the birds had mid-size bills. The finches appeared to be in the early stages of a new adaptive radiation: If the trend continued, the medium ground finch on Santa Cruz could split into two distinct subspecies, specializing in different types of seeds. But in the late 1960s and early 70s, medium ground finches with medium-sized bills began to thrive at Academy Bay along with small and large-billed birds. The booming human population had introduced new food sources, including exotic plants and bird feeding stations stocked with rice. Billsize, once critical to the finches’ survival, no longer made any difference. ‘Now an intermediate bill can do fine,’ Hendry says.

J

At a control site distant from Puerto Ayora, and relatively untouched by humans, the medium ground finch population remains split between large- and small-billed birds. On undisturbed parts of Santa Cruz, there is no ecological niche for a middling medium ground finch, and the birds continue to diversify. In town, though there are still many finches, once- distinct populations are merging.

K

The finches of Santa Cruz demonstrate a subtle process in which human meddling can stop evolution in its tracks, ending the formation of new species. In a time when global biodiversity continues its downhill slide, Darwin’s finches have yet another unexpected lesson to teach. ‘If we hope to regain some of the diversity that’s already been lost/ Hendry says, ‘we need to protect not just existing creatures, but also the processes that drive the origin of new species.

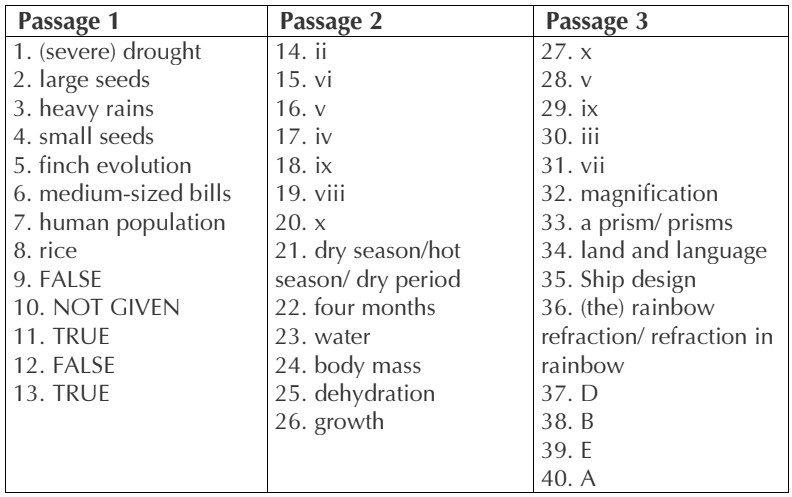

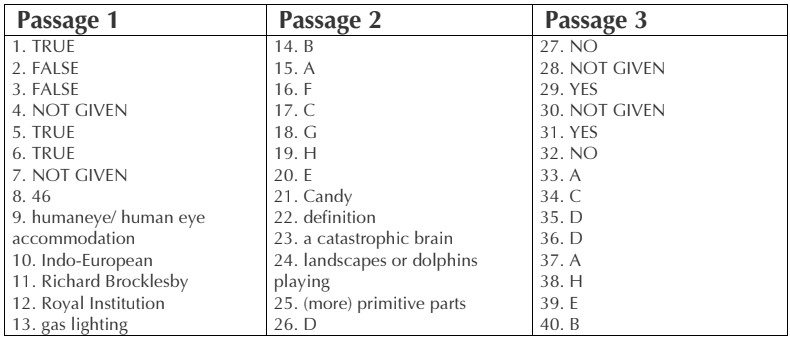

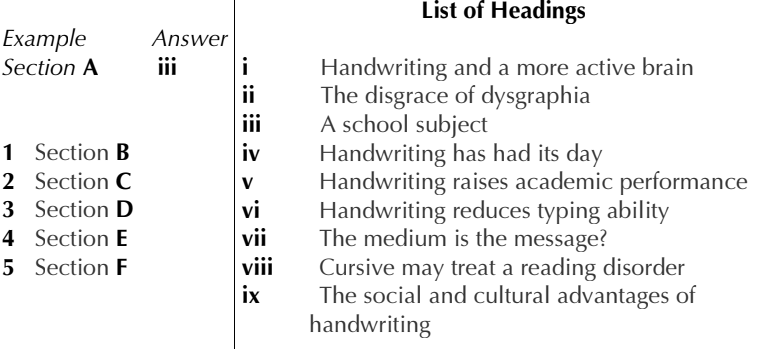

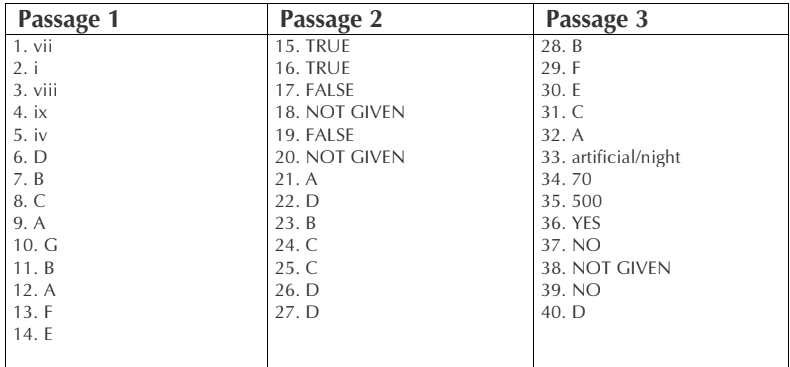

Questions 1- 4 :

Questions 5 – 8: Use NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS for each

answer.

On the remote island of Santa Cruz, Andrew Hendry and Jeffrey Podos conducted a study on reversal 5………………… due to human activity. In the early 1960s medium ground finches were found to have a larger or smaller beak. But in the late 1960s and early 70s, finches with 6………………… flourished. The study speculates that it is due to the growing 7………………… who brought in alien plants with intermediate- size seeds into the area and the birds ate 8………………… sometimes.

Questions 10-13 TRUE – FALSE – NOT GIVEN

9/ Grants’ discovery has questioned Darwin’s theory.

10/ The cactus finches are less affected by food than the medium ground

finch.

11/ In 2002 and 2003, all the birds were affected by the drought.

12/ The discovery of Andrew Hendry and Jeffrey Podos was the same as

that of the previous studies.

13/ It is shown that the revolution in finches on Santa Cruz is likely a

response to human intervention.

2- The evolutional mystery: Crocodile survives

A

Crocodiles have been around for 200 million years, but they’re certainly not primitive. The early forms of crocodiles are known as Crocodilian. Since they spent most of their life beneath water, accordingly their body adapted to aquatic lifestyle. Due to the changes formed within their body shape and tendency to adapt according to the climate they were able to survive when most of the reptiles of their period are just a part of history. In their tenure on Earth, they’ve endured the impacts of meteors, planetary refrigeration, extreme upheavals of the Earth’s tectonic surface and profound climate change. They were around for the rise and fall of the dinosaurs, and even 65 million years of supposed mammalian dominance has failed to loosen their grip on the environments they inhabit. Today’s crocodiles and alligators are little changed from their prehistoric ancestors, a telling clue that these reptiles were (and remain) extremely well adapted to their environment.

B

The first crocodile-like ancestors appeared about 230 million years ago, with many of the features that make crocs such successful stealth hunters already in place: streamlined body, long tail, protective armour and long jaws. They have long head and a long tail that helps them to change their direction in water while moving. They have four legs which are short and are webbed. Never underestimate their ability to move on ground. When they move they can move at such a speed that won’t give you a second chance to make a mistake by going close to them especially when hungry. They can lift their whole body within seconds from ground. The fastest way by which most species can move is a sort of “belly run”, where the body moves like a snake, members huddled to the side paddling away frenetically while the tail whips back and forth. When “belly running” Crocodiles can reach speeds up to 10 or 11 km/h (about 7mph), and often faster if they are sliding down muddy banks. Other form of movement is their “high walk”, where the body is elevated above the ground.

C

Crocodilians have no lips. When submerged in their classic ‘sit and wait’ position, their mouths fill with water. The nostrils on the tip of the elongated snout lead into canals that run through bone to open behind the valve – allowing the crocodilian to breathe through its nostrils even though its mouth is under water. When the animal is totally submerged, another valve seals the nostrils, so the crocodilian can open its mouth to catch prey with no fear of drowning. The thin skin on the crocodilian head and face is covered with tiny, pigmented domes, forming a network of neural pressure receptors that can detect barely perceptible vibrations in the water. This enables a crocodile lying in silent darkness to suddenly throw its head sideways and grasp with deadly accuracy small prey moving close by.

D

Like other reptiles, crocodiles are endothermic animals (cold-blooded, or whose body temperature varies with the temperature of the surrounding environment) and, therefore, need to sunbathe, to raise the temperature of the body. On the contrary, if it is too hot, they prefer being in water or in the shade. Being a cold-blooded species, the crocodilian heart is unique in having an actively controlled valve that can redirect, at will, blood flow away from the lungs and recirculate it around the body, taking oxygen to where it’s needed most. In addition, their metabolism is a very slow one, so, they can survive for long periods without feeding. Crocodiles are capable of slowing their metabolism even further allowing them to survive for a full year without feeding. Compared to mammals and birds, crocodilians have slow metabolisms that burn much less fuel, and are ideally suited to relatively unstable environments that would defeat mammals with their high food demands.

E

Crocodiles use a very effective technique to catch the prey. The prey remains almost unaware of the fact that there can be any crocodile beneath water. It is due to the fact that when the crocodile sees its prey it moves under water without making any noise and significant movement. It keeps only its eyes above water surface. When it feels it has reached sufficiently close to the target it whistles out of water with wide open jaws. 80 percent of their attempts are successful. They have very powerful jaws. Once the prey trapped in its jaws they swallow it. Their power can be judged from the fact they can kill the wild zebras which come to watery areas in search of water. They do not chew their food. They normally feed on small animals, big fish, birds and even human flesh. As like some water creatures that interact by making sounds crocodiles also use many sounds to communicate with other crocodiles. They exist where conditions have remained the same and they are free of human interference. The crocodile is successful because it switches its feeding methods. It hunts fish, grabs birds at the surface, hides among the water edge vegetation to wait for a gazelle to come by, and when there is a chance for an ambush, the crocodile lunges forward, knocks the animal with its powerful tail and then drags it to water where it quickly drowns. Another way is to wait motionless for an animal to come to the water’s edge and grabs it by its nose where it is held to drown.

F

In many places inhabited by crocodilians, the hot season brings drought that dries up their hunting grounds and takes away the means to regulate their body temperature. They allowed reptiles to dominate the terrestrial environment. Furthermore, many crocs protect themselves from this by digging burrows and entombing themselves in mud, waiting for months without access to food or water, until the rains arrive. To do this, they sink into a quiescent state called aestivation.

G

Most of (At least nine species of) crocodilian are thought to aestivate during dry periods. Kennett and Christian’s six-year study of Australian freshwater crocodiles – Crocodylus johnstoni (the King Crocodiles). The crocodiles spent almost four months a year underground without access to water. Doubly labeled water was used to measure field metabolic rates and water flux, and plasma (and cloacal fluid samples were taken at approximately monthly intervals during some years to monitor the effects of aestivation with respect to the accumulation of nitrogenous wastes and electrolyte concentrations. Double found that the crocodiles’ metabolic engines tick over, producing waste and using up water and fat reserves. Waste products are stored in the urine, which gets increasingly concentrated as the months pass. However, the concentration of waste products in the blood changes very little, allowing the crocodiles to function normally. Furthermore, though the animals lost water and body mass (just over one-tenth of their initial mass) while underground, the losses were proportional: on emergence, the aestivating crocodiles were not dehydrated and exhibited no other detrimental effects such as a decreased growth rate. Kennett and Christian believe this ability of individuals to sit out the bad times and endure long periods of enforced starvation must surely be key to the survival of the crocodilian line through time.

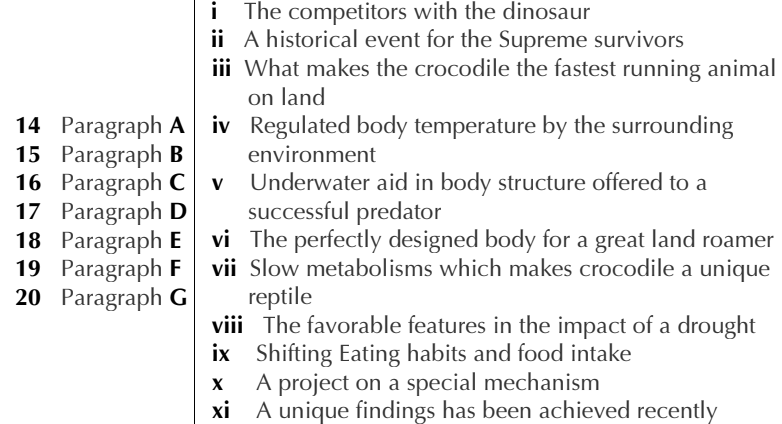

Questions 14-20:

Questions 21-26 Complete the summary and write the correct answer (NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS OR A NUMBER)

In many places inhabited by crocodilians, most types of the crocodile have evolved a successful scheme to survive in the drought brought by a 21……………………… According to Kennett and Christian’s six-year study of Australian freshwater crocodiles’ aestivation, they found Aestivating crocodiles spent around 22……………………… a year without access to 23……………………… The absolute size of body water pools declined proportionately with 24………………………; thus there is no sign of 25……………………… and other health-damaging impact in the crocodiles even after an aestivation period. This super capacity helps crocodiles endure the tough drought without slowing their speed of 26……………………… significantly.

3 – Thomas Harriot The Discovery of Refraction

A

When light travels from one medium to another, it generally bends, or refracts. The law of refraction gives us a way of predicting the amount of bending. Refraction has many applications in optics and technology. A lens uses refraction to form an image of an object for many different purposes, such as magnification. A prism uses refraction to form a spectrum of colors from an incident beam of light. Refraction also plays an important role in the formation of a mirage and other optical illusions. The law of refraction is also known as Snell’s Law, named after Willobrord Snell, who discovered the law in 1621. Although Snell’s sine law of refraction is now taught routinely in undergraduate courses, the quest for it spanned many centuries and involved many celebrated scientists. Perhaps the most interesting thing is that the first discovery of the sine law, made by the sixteenth-century English scientist Thomas Harriot (1560-1621), has been almost completely overlooked by physicists, despite much published material describing his contribution.

B

A contemporary of Shakespeare, Elizabeth I, Johannes Kepler and Galilei Galileo, Thomas Harriot (1560-1621) was an English scientist and mathematician. His principal biographer, J. W. Shirley, was quoted saying that in his time he was “England’s most profound mathematician, most imaginative and methodical experimental scientist”. As a mathematician, he contributed to the development of algebra, and introduced the symbols of ”>”, and ”<” for ”more than” and ”less than.” He also studied navigation and astronomy. On September 17, 1607, Harriot observed a comet, later Identified as Hailey-s. With his painstaking observations, later workers were able to compute the comet’s orbit. Harriot was also the first to use a telescope to observe the heavens in England. He made sketches of the moon in 1609, and then developed lenses of increasing magnification. By April 1611, he had developed a lens with a magnification of 32. Between October 17, 1610 and February 26, 1612, he observed the moons of Jupiter, which had already discovered by Galileo. While observing Jupiter’s moons, he made a discovery of his own: sunspots, which he viewed 199 times between December 8, 1610 and January 18, 1613. These observations allowed him to figure out the sun’s period of rotation.

C

He was also an early English explorer of North America. He was a friend of the English courtier and explorer Sir Walter Raleigh and travelled to Virginia as a scientific observer on a colonising expedition in 1585. On June 30, 1585, his ship anchored at Roanoke Island ,off Virginia. On shore, Harriot observed the topography, flora and fauna, made many drawings and maps, and met the native people who spoke a language the English called Algonquian. Harriot worked out a phonetic transcription of the native people’s speech sounds and began to learn the language, which enabled him to converse to some extent with other natives the English encountered. Harriot wrote his report for Raleigh and published it as A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia in 1588. Raleigh gave Harriot his own estate in Ireland, and Harriot began a survey of Raleigh’s Irish holdings. He also undertook a study of ballistics and ship design for Raleigh in advance of the Spanish Armada’s arrival.

D

Harriot kept regular correspondence with other scientists and mathematicians, especially in England but also in mainland Europe, notably with Johannes Kepler. About twenty years before Snell’s discovery, Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) had also looked for the law of refraction, but used the early data of Ptolemy. Unfortunately, Ptolemy’s data was in error, so Kepler could obtain only an approximation which he published in 1604. Kepler later tried to obtain additional experimental results on refraction, and corresponded with Thomas Harriot from 1606 to 1609 since Kepler had heard Harriot had carried out some detailed experiments. In 1606, Harriot sent Kepler some tables of refraction data for different materials at a constant incident angle, but didn’t provide enough detail for the data to be very useful. Kepler requested further information, but Harriot was not forthcoming, and it appears that Kepler eventually gave up the correspondence, frustrated with Harriot’s reluctance.

E

Apart from the correspondence with Kepler, there is no evidence that Harriot ever published his detailed results on refraction. His personal notes, however, reveal extensive studies significantly predating those of Kepler, Snell and Descartes. Harriot carried out many experiments on refraction in the 1590s, and from his notes, it is clear that he had discovered the sine law at least as early as 1602. Around 1606, he had studied dispersion in prisms (predating Newton by around 60 years), measured the refractive indices of different liquids placed in a hollow glass prism, studied refraction in crystal spheres, and correctly understood refraction in the rainbow before Descartes.

F

As his studies of refraction, Harriot’ s discoveries in other fields were largely unpublished during his lifetime, and until this century, Harriot was known only for an account of his travels in Virginia published in 1588, , and for a treatise on algebra published posthumously in 1631. The reason why Harriot kept his results unpublished is unclear. Harriot wrote to Kepler that poor health prevented him from providing more information, but it is also possible that he was afraid of the seventeenth century’s English religious establishment which was suspicious of the work carried out by mathematicians and scientists.

G

After the discovery of sunspots, Harriot’ s scientific work dwindled. The cause of his diminished productivity might have been a cancer discovered on his nose. Harriot died on July 2, 1621, in London, but his story did not end with his death. Recent research has revealed his wide range of interests and his genuinely original discoveries. What some writers describe as his “thousands upon thousands of sheets of mathematics and of scientific observations” appeared to be lost until 1784, when they were found in Henry Percy’s country estate by one of Percy’s descendants. She gave them to Franz Xaver Zach, her husband’s son’s tutor. Zach eventually put some of the papers in the hands of the Oxford University Press, but much work was required to prepare them for publication, and it has never been done. Scholars have begun to study them,, and an appreciation of Harriot’s contribution started to grow in the second half of the twentieth century. Harriot’s study of refraction is but one example where his work overlapped with independent studies carried out by others in Europe, but in any historical treatment of optics his contribution rightfully deserves to be acknowledged.

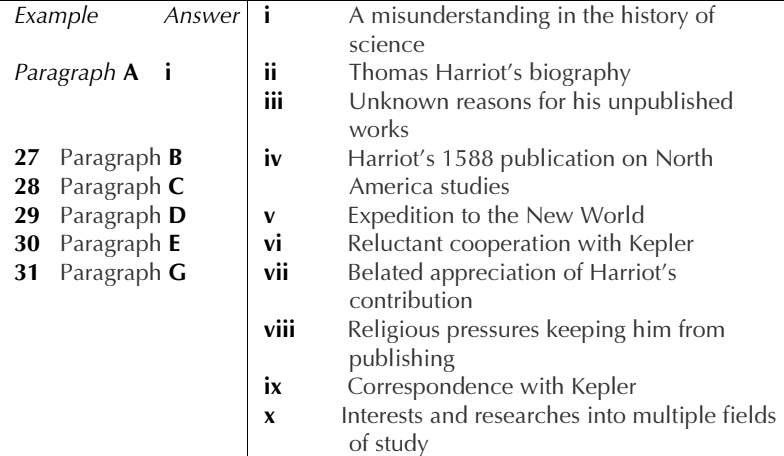

Questions 27-31:

Questions 32-36:

Various modem applications base on an image produced by lens uses refraction, such as 32…………………. And a spectrum of colors from a beam of light can be produced with 33…………………. Harriot travelled to Virginia and mainly did research which focused on two subjects of American 34…………………. After, he also enters upon a study of flight dynamics and 35…………………. for one of his friends much ahead of major European competitor. He undertook extensive other studies which were only noted down personally yet predated than many other great scientists. One result, for example, corrected the misconception about the idea of 36………………….

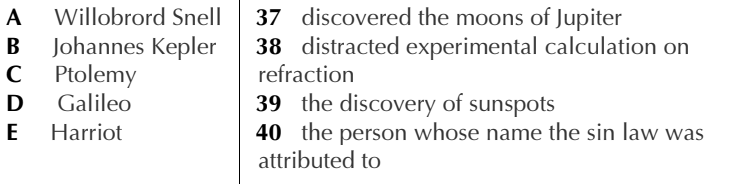

Questions 37-40: