- Passage 1: Video Practice Test!

- Passage 2: Video Practice Test!

- Passage 3: Video Practice Test!

1 – Spider silk

A strong, light bio-material made by genes from spiders could transform construction and industry

A

Scientists have succeeded in copying the silk-producing genes of the Golden Orb Weaver spider and are using them to create a synthetic material which they believe is the model for a new generation of advanced bio-materials. The new material, biosilk, which has been spun for the first time by researchers at DuPont, has an enormous range of potential uses in construction and manufacturing.

B

The attraction of the silk spun by the spider is a combination of great strength and enormous elasticity, which man-made fibres have been unable to replicate. On an equal-weight basis, spider silk is far stronger than steel and it is estimated that if a single strand could be made about 10m in diameter, it would be strong enough to stop a jumbo jet in flight. A third important factor is that it is extremely light. Army scientists are already looking at the possibilities of using it for lightweight, bulletproof vests and parachutes.

C

For some time, biochemists have been trying to synthesise the drag- line silk of the Golden Orb Weaver. The drag-line silk, which forms the radial arms of the web, is stronger than the other parts of the web and some biochemists believe a synthetic version could prove to be as important a material as nylon, which has been around for 50 years, since the discoveries of Wallace Carothers and his team ushered in the age of polymers.

D

To recreate the material, scientists, including Randolph Lewis at the University of Wyoming, first examined the silk-producing gland of the spider. ‘We took out the glands that produce the silk and looked at the coding for the protein material they make, which is spun into a web. We then went looking for clones with the right DNA,’ he says.

E

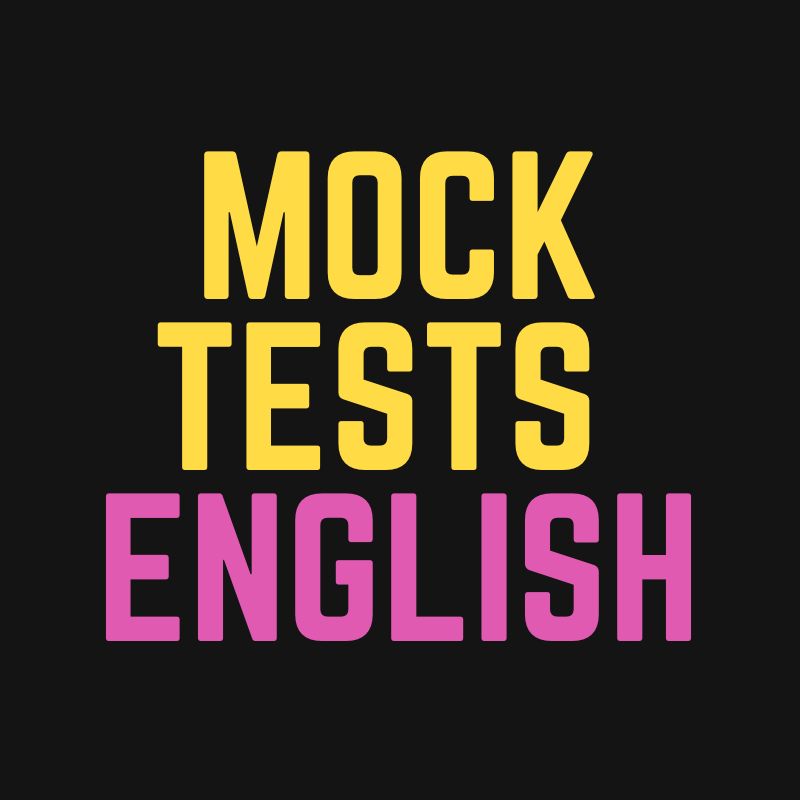

At DuPont, researchers have used both yeast and bacteria as hosts to grow the raw material, which they have spun into fibres. Robert Dorsch, DuPont’s director of biochemical development, says the globules of protein, comparable with marbles in an egg, are harvested and processed. ‘We break open the bacteria, separate out the globules of protein and use them as the raw starting material. With yeast, the gene system can be designed so that the material excretes the protein outside the yeast for better access,’ he says.

F

‘The bacteria and the yeast produce the same protein, equivalent to that which the spider uses in the draglines of the web. The spider mixes the protein into a water-based solution and then spins it into a solid fibre in one go. Since we are not as clever as the spider and we are not using such sophisticated organisms, we substituted man-made approaches and dissolved the protein in chemical solvents, which are then spun to push the material through small holes to form the solid fibre.’

G

Researchers at DuPont say they envisage many possible uses for a new biosilk material. They say that earthquake-resistant suspension bridges hung from cables of synthetic spider silk fibres may become a reality. Stronger ropes, safer seat belts, shoe soles that do not wear out so quickly and tough new clothing are among the other applications. Biochemists such as Lewis see the potential range of uses of biosilk as almost limitless. ‘It is very strong and retains elasticity: there are no man-made materials that can mimic both these properties. It is also a biological material with all the advantages that have over petrochemicals,’ he says.

H

At DuPont’s laboratories, Dorsch is excited by the prospect of new super-strong materials but he warns they are many years away. ‘We are at an early stage but theoretical predictions are that we will wind up with a very strong, tough material, with an ability to absorb shock, which is stronger and tougher than the man-made materials that are conventionally available to us,’ he says.

I

The spider is not the only creature that has aroused the interest of material scientists. They have also become envious of the natural adhesive secreted by the sea mussel. It produces a protein adhesive to attach itself to rocks. It is tedious and expensive to extract the protein from the mussel, so researchers have already produced a synthetic gene for use in surrogate bacteria.

Questions 1 – 5

Which section A – I contains the following information?

1/ a comparison of the ways two materials are used to replace silk-

producing glands

2/ predictions regarding the availability of the synthetic silk

3/ ongoing research into other synthetic materials

4/ the research into the part of the spider that manufactures silk

5/ the possible application of the silk in civil engineering

Questions 6-10

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer

Questions 11 – 13: TRUE – FALSE – NOT GIVEN.

11/ Biosilk has already replaced nylon in parachute manufacture.

12/ The spider produces silk of varying strengths.

13/ Lewis and Dorsch co-operated in the synthetic production of silk

2- Novice and Expert – Becoming an Expert

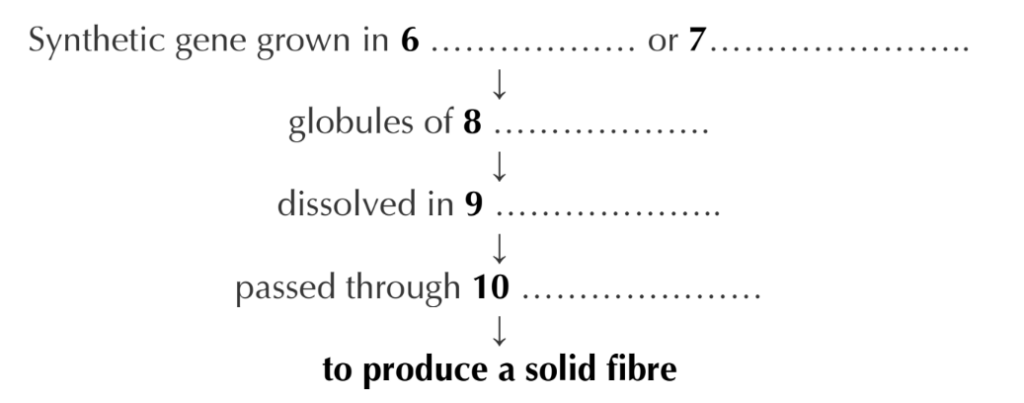

Expertise is commitment coupled with creativity. Specifically, it is the commitment of time, energy, and resources to a relatively narrow field of study and the creative energy necessary to generate new knowledge in that field. It takes a considerable amount of time and regular exposure to a large number of cases to become an expert.

A

An individual enters a field a study as a novice. The novice needs to learn the guiding principles and rules of a given task in order to perform that task. Concurrently, the novice needs to be exposed to specific cases, or instances, that test the boundaries of such heuristics. Generally, a novice will find a mentor to guide her through the process. A fairly simple example would be someone learning to play chess. The novice chess player seeks a mentor to teach her the object of the game, the number of spaces, the names of the pieces, the function of each piece, how each piece is moved, and the necessary conditions for winning or losing the game.

B

In time, and with much practice, the novice begins to recognize patterns of behavior within cases and, thus, becomes a journeyman. With more practice and exposure to increasingly complex cases, the journeyman finds patterns not only with cases but also between cases. More importantly, the journeyman learns that these patterns often repeat themselves over time. The journeyman still maintains regular contact with a mentor to solve specific problems and learn more complex strategies. Returning to the example of the chess player, the individual begins to learn patterns of opening moves, offensive and defensive game-playing strategies, and patterns of victory and defeat.

C

When a journeyman starts to make and test hypotheses about future behavior based on past experiences, she begins the next transition. Once she creatively generates knowledge, rather than simply matching superficial patterns, she becomes an expert. At this point, she is confident in her knowledge and no longer needs a mentor as a guide – she becomes responsible for her own knowledge. In the chess example, once a journeyman begins competing against experts, makes predictions based on patterns, and tests those predictions against actual behavior, she is generating new knowledge and a deeper understanding of the game. She is creating her own cases rather than relying on the cases of others. The Power of Expertise

D

An expert perceives meaningful patterns in her domain better than non-experts. Where a novice perceives random or disconnected date points, an expert connects regular patterns within and between cases. This ability to identify patterns is not an innate perceptual skill; rather it reflects the organization of knowledge after exposure to and experience with thousands of cases. Experts have a deeper understanding of their domains than novices do, and utilize higher- order principles to solve problems. A novice, for example, might group objects together by color or size, whereas an expert would group the same objects according to their function or utility. Experts comprehend the meaning of data and weigh variables with different criteria within their domains better than novices. Experts recognize variables that have the largest influence on a particular problem and focus their attention on those variables.

E

Experts have better domain-specific short-term and long-term memory than novices do. Moreover, experts perform tasks in their domains faster than novices and commit fewer errors while problem solving. Interestingly, experts go about solving problems differently than novices. Experts spend more time thinking about a problem to fully understand it at the beginning of a task than do novice, who immediately seek to find a solution. Experts use their knowledge of previous cases as a context for creating mental models to solve given problems.

F

Better at self-monitoring than novices, experts are more aware of instances where they have committed errors or failed to understand a problem. Experts check their solutions more often than novices and recognize when they are missing information necessary for solving a problem. Experts are aware of the limits of their domain knowledge and apply their domain’s heuristics to solve problems that fall outside of their experience base. The Paradox of Expertise

G

The strengths of expertise can also be weakness. Although one would expect experts to be good forecasters, they are not particularly good at making predictions about the future. Since the 1930s, researchers have been testing the ability of experts to make forecasts. The performance of experts has been tested against actuarial tables to determine if they are better at making predictions than simple statistical models. Seventy years later, with more than two hundred experiments in different domains, it is clear that the answer is no. if supplied with an equal amount of data about a particular case, an actuarial table is as good, or better, than an expert at making calls about the future. Even if an expert is given more specific case information than is available to the statistical model, the expert does not tend to outperform the actuarial table.

H Theorists and researchers differ when trying to explain why experts are less accurate forecasters than statistical models. Some have argued that experts, like all humans, are inconsistent when using mental models to make predictions. A number of researchers point to human biases to explain unreliable expert predictions. A number of researchers point to human biases to explain unreliable expert predictions. During the last 30 years, researchers have categorized, experimented, and theorized about the cognitive aspects of forecasting. Despite such efforts, the literature shows little consensus regarding the causes or manifestation of human bias.

Questions 14 – 18:

Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Questions 19 – 23: TRUE – FALSE – NOT GIVEN

19/ Novices and experts use the same system to classify objects.

20/ A novice’s training is focused on memory skills.

21/ Experts have higher efficiency than novices when solving problems in

their own field.

22/ When facing a problem, a novice always tries to solve it straight away.

23/ Experts are better at recognizing their own mistakes and limits

Questions 24 – 26:

Choose NO MORE THAN 2 WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Though experts are quite effective at solving problems in their own

domains, their strengths can also be turned against them. Studies have

shown that experts are less 24………………….. at making predictions than statistical models. Some researchers theorise it is because experts can also be inconsistent like all others. Yet some believe it is due to 25………………., but there isn’t a great deal of 26………………… as to its cause and manifestation.

3 – Inside the mind of a fan How watching sport affects the brain

A

At about the same time that the poet Homer invented the epic here, the ancient Greeks started a festival in which men competed in a single race, about 200 metres long. The winner received a branch of wild olives. The Greeks called this celebration the Olympics. Through the ancient sprint remains, today the Olympics are far more than that. Indeed, the Games seem to celebrate the dream of progress as embodied in the human form. That the Games are intoxicating to watch is beyond question. During the Athens Olympics in 2004, 3.4 billion people, half the world, watched them on television. Certainly, being a spectator is a thrilling experience: but why?

B

In 1996, three Italian neuroscientists, Giacomo Rizzolatti, Leonardo Forgassi and Vittorio Gallese, examined the premotor cortex of monkeys. The discovered that inside these primate brains there were groups of cells that ‘store vocabularies of motor actions’. Just as there are grammars of movement. These networks of cells are the bodily ‘sentences’ we use every day, the ones our brain has chosen to retain and refine. Think, for example, about a golf swing. To those who have only watched the Master’s Tournament on TV, golfing seems easy. To the novice, however, the skill of casting a smooth arc with a lop-side metal stick is virtually impossible. This is because most novices swing with their consciousness, using an area of brain next to the premotor cortex. To the expert, on the other hand, a perfectly balanced stroke is second nature. For him, the motor action has become memorized, and the movements are embedded in the neurons of his premotor cortex. He hits the ball with the tranquility of his perfected autopilot.

C

These neurons in the premotor cortex, besides explaining why certain athletes seem to possess almost unbelievable levels of skill, have an even more amazing characteristic, one that caused Rizzolatti, Fogassi and Gallese to give them the lofty title ‘mirror neurons’. They note, The main functional characteristic of mirror neurons is that they become active both when the monkey performs a particular action (for example, grasping an object or holding it) and, astonishingly, when it sees another individual performing a similar action.’ Humans have an even more elaborate mirror neuron system. These peculiar cells mirror, inside the brain, the outside world: they enable us to internalize the actions of another. In order to be activated, though, these cells require what the scientists call ‘goal-orientated movements’. If we are staring at a photograph, a fixed image of a runner mid-stride, our mirror neurons are totally silent. They only fire when the runner is active: running, moving or sprinting.

D

What these electrophysiological studies indicate is that when we watch a golfer or a runner in action, the mirror neurons in our own premotor cortex light up as if we were the ones competing. This phenomenon of neural mirror was first discovered in 1954, when two French physiologists, Gastaut and Berf, found that the brains of humans vibrate with two distinct wavelengths, alpha and mu. The mu system is involved in neural mirroring. It is active when your bodies are still, and disappears whenever we do something active, like playing a sport or changing the TV channel. The surprising fact is that the mu signal is also quiet when we watch someone else being active, as on TV, these results are the effect of mirror neurons.

E

Rizzolatti, Fogassi and Gallese call the idea for mirror neurons the ‘direct matching hypothesis’. They believe that we only understand the movement of sports stars when we ‘map the visual representation of the observed action onto our motor representation of the same action’. According to this theory, watching an Olympic athlete ‘causes the motor system of the observer to resonate. The “motor knowledge” of the observer is used to understand the observed action.’ But mirror neurons are more than just the neural basis for our attitude to sport. It turns out that watching a great golfer makes us better golfers, and watching a great sprinter actually makes us run faster. This ability to learn by watching is a crucial skill. From the acquisition of language as infants to learning facial expressions, mimesis (copying) is an essential part of being conscious. The best athletes are those with a premotor cortex capable of imagining the movements of victory, together with the physical properties to make those movements real.

F

But how many of us regularly watch sports in order to be a better athlete? Rather, we watch sport for the feeling, the human drama. This feeling also derives from mirror neurons. By letting spectators share in the motions of victory, they also allow us to share in its feelings. This is because they are directly connected to the amygdale, one of the main brain regions involved in emotion. During the Olympics, the mirror neurons of whole nations will be electrically identical, their athletes causing spectators to feel, just for a second or two, the same thing. Watching sports brings people together. Most of us will never run a mile in under four minutes, or hit a home run. Our consolation comes in watching, when we gather around the TV, we all feel, just for a moment, what it is to do something perfectly.

Questions 27 – 32:

Which paragraph A – F contains the following information?

27/ an explanation of why watching sport may be emotionally satisfying

28/ an explanation of why beginners find sporting tasks difficult

29/ a factor that needs to combine with mirroring to attain sporting

excellence

30/ a comparison of human and animal mirror neurons

31/ the first discovery of brain activity related to mirror neurons

32/ a claim linking observation to improvement in performance

Questions 33 – 35:

33/ The writer uses the term ‘grammar of movement’ to mean

A a level of sporting skill.

B a system of words about movement.

C a pattern of connected cells.

D a type of golf swing.

34/ The writer states that expert players perform their actions

A without conscious thought.

B by planning each phase of movement.

C without regular practice.

D by thinking about the actions of others.

35/ The writer states that the most common motive for watching sport is

to

A improve personal performance.

B feel linked with people of different nationalities.

C experience strong positive emotions.

D realize what skill consists of.

Questions 36-40: YES – NO – NOT GIVEN

36/ Inexpert sports players are too aware of what they are doing.

37/ Monkeys have a more complex mirror neuron system than humans.

38/ Looking at a photograph can activate mirror neurons.

39/ Gastaut and Bert were both researchers and sports players.

40/ The mu system is at rest when we are engaged in an activity.